Plants of the Tundra Biome: How Unique Species Thrive in Harsh Conditions

Plants of the Tundra Biome

The tundra is one of the most inhospitable biomes on Earth. Long winters and very short summers, low temperatures, poor penetration of sunlight, and modest precipitation levels all spell disaster for plant life. However, thousands of specialized plant species still manage to thrive. How, exactly? Read on to find out.

Tundra is a northern, cold biome that stretches across different parts of the world and is known for its rolling, rocky, treeless landscape covered in low vegetation.

What Are The Two Types of Tundra?

There are two forms of tundra, depending on their location.

- Arctic tundra includes vast tracts of land in polar and subpolar regions of the Eurasian and North American continents.

- The high-latitude parts of Canada, Iceland, Greenland, Europe (Scandinavia), Russia, and the US (Alaska) all host the tundra biome within their perimeters.

- Alpine tundra ecosystems are found on tall mountains at high elevations and are scattered across different parts of temperate-climate continents.

- Notable Alpine tundra examples include The Himalayas, The Tibetan Plateau, The Caucasus Mountains (Asia), The Rift Mountains (Africa), the American Cordillera (the Americas), the Alps, the Pyrenees, and Scandes Mountains (Europe).

What Are The Climatic Conditions In The Tundra Biome?

Tundra is often called “the desert of ice” – with a good reason.

- Temperatures in the tundra range between 3 to 12 °C (37 to 54 °F) in the summertime and down to –18 °C (0 °F) in the wintertime; temperatures below 0°C can last from 6 to 10 months per year.

- Tundra receives very little precipitation – only about 25 centimeters (10 inches) annually.

- Tundra has harsh winds that would likely break or top over any tree-like plant life – even if it was able to grow due to other circumstances.

- Tundra’s soil profile is predominantly made of permafrost – permanently frozen ground. The roots are not able to penetrate or survive in the permafrost zone.

- That little bit of loose soil on top of all the permafrost is very poor in essential nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, stunting plant growth.

That sounds bleak already, but it becomes nearly shocking if we sum it up like this: in the tundra, only six to ten weeks per year are warm and light enough to enable plant growth!

Still, despite what seems to be impossible conditions, the tundra features more than 1700 plant species – mosses, liverworts, grasses, sedges, and low shrubs. While that is still a low diversity rate compared to other biomes, the tundra plants are still surviving and thriving in the “icy desert.” Most of them are unique and have had to evolve particular adaptations to beat the weather.

So, what are the unique plant adaptations to life in the tundra?

We’ll introduce you to some weird and wonderful plant species and analyze what made them successful in their extreme habitat.

Dwarf Willow (Salix herbacea)

Dwarf Willow (Salix herbacea)

Аdaptation: small, low growth; broad leaves

The common names of the dwarf willow or least willow undoubtedly announce that this is one small willow. In fact, Salix herbacea is one of the smallest woody plants in the world, standing only 1 to 6 centimeters (0,5 to 2,5 inches) above the ground.

Small growth has many advantages in inhospitable environments like the tundra. A low growing mini-plant:

- Doesn’t require large amounts of basic elements like water or nutrients.

- Will not break under the influence of infamous tundra winds.

- Has a shallow root system that can anchor the plant and draw in the nutrients despite the fact that the ground is frozen (in the form of permafrost).

The dwarf willow has other tricks it uses to survive. For example, it has broad leaves – broader than other willow species – to maximize the absorption of the scarce northern sunlight.

Did you know?

One of the main traits of the tundra landscape is that it is treeless. In fact, the term “tundra” comes from the Finish word “tunturia” which means “barren, treeless hill.”

Tall trees wouldn’t be able to thrive in the tundra precisely for the reasons that have kept the Dwarf willow evolutionary small – they require way too much water and nutrients than the habitat can offer, they wouldn’t be able to grow roots in the permafrost, and the high winds would easily break or top them over.

Pasqueflower (Pulsatilla patens)

Adaptation: hairy growth

Pasqueflower is a jewel of the North American tundra – the cup-shaped, white, pinkish, bluish, or dark-purple flowers grow on southern slopes only.

However, despite inhabiting the warmer south side, Pasqueflower still needs additional protection from the freezing weather.

Fine, dense hairs covering the plant actually insulate it from the frost and the cold – similar to animal fur. The fuzz works exceptionally well to protect the plants from the high-freezing wind.

This adaptation is found in many other tundra plants such as Cottongrass (Eriophorum vaginatum), Arctic Willow (Salix arctica), and Arctic Lupine (Lupinus arcticus). In fact, hairs can be found in most plants featured on this list, so don’t be surprised we’ll be using the word a lot.

A word of caution: belonging to the buttercup family, Pasqueflower is toxic – it shouldn’t be handled, let alone consumed, as it can cause a severe reaction. You should marvel at its beauty from a safe distance.

Arctic Crocus (Anemone patens)

Adaptation: clumping together; hair

Another flowery attraction of the biome, the arctic crocus, has bicolor flowers that come in a combination of purple and white – contrasted by bright yellow-to-orange stamen typical to all crocus species.

Like the pasqueflower, the arctic crocus also grows short, dense hairs on all its aboveground parts – leaves, buds, and stems – to lessen the impact of the cold weather. There is another adaptive trait – individual plants grow closer together than the temperate crocus species. That way, they can stay warmer and avoid some freezing wind effects.

Arctic Poppy (Papaver radicatum)

Adaptation: Root runners.

This North American poppy is present in the Arctic and various alpine regions. The main part of the plant grows close to the ground – it’s just the flower stems that stick out about 10 centimeters above. The flowers have a light-yellow color, quite unique in the world of wild poppies.

Unlike many other tundra plants that have very small root systems, the Arctic poppy has a different strategy – its root system is made out of runners spread over a wide area. That way, the plant can “find” and access the scarce water over a relatively large area.

Moss Campion (Silene acaulis)

Adaptation: ground-covering cushion shape

Moss campion is one of the northern Arctic’s most common plants and is also present in alpine tundra regions. Because it is so common, it is one of the trademarks of the tundra landscape, decorating it with its prolific pinkish flowers during the bloom time.

However, it is the shape of this plant that we’re interested in.

The characteristic cushion shape enables the plant almost hug the ground, thereby retaining heat. When the weather warms up, the temperature inside of the “cushion” is truly, measurably warmer than the environment.

Additionally, the small size of the leaves ensures they won’t be damaged by the frost and the wind.

Interestingly, the Moss campion is sometimes called “the compass plant” because the blooms first appear on the southern side of the plant.

Alpine Sunflower (Hymenoxys grandiflora)

Adaptation: Non-rotating flowers; hairs

This attractive sunflower cousin is native to the alpine tundra regions of the western United States – specifically, the heights of the Rockies.

In general, sunshine in the polar tundra is rare and precious, and some plants (see the pasqueflower) have darker blooms to capture as much of the sun’s energy as possible.

However, the alpine tundra is a bit different. Because of the elevation, the solar radiation can get very intense at midday, especially during the summer – and the UV radiation can be damaging. That is likely the reason why the showy inflorescences of the Alpine sunflower do not rotate towards the sun.

The Alpine sunflower is also in the tundra hairy plants club – its foliage is covered in cottony white hairs.

Cottongrass (Eriophorum vaginatum)

Adaptations: Fluffy seedpods

Cottongrass is commonly found in the tundra biome worldwide, and can also be found in peatlands elsewhere. Despite its name, Cottongrass is not a true grass – it belongs to the family of sedges – grass-like monocots.

The plant is distinct for its fluffy, cotton-like seed heads. However, these are not a mere decoration, but a way to efficiently utilize the infamous tundra winds to spread the seeds and carry them to great distances.

Also, the hairy fluff likely helps to trap some heat and protect the seeds from the cold.

Labrador Tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum)

Adaptations: Leaf modifications

This low flowering shrub is typical of cool North American areas, all the way to Greenland. Used as an herbal tea since ancient times – hence the name – the Labrador tea has many leaf adaptations that help it survive the harsh cold and remain evergreen.

The oval leaves are small, narrow, and thick, with edges curved inwards. Also, they have a dense mat of small hairs on their undersides. Scientists are still debating if these are adaptations to the cold, the drought, or the lack of nutrients – but all those evolutionary pressures are characteristic of the tundra biome anyway.

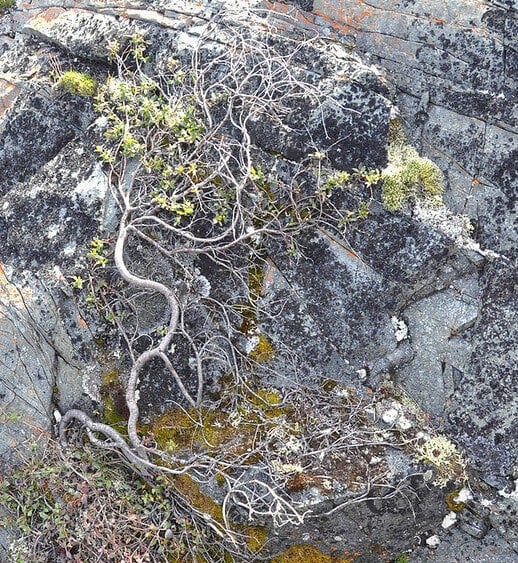

Tufted Saxifrage (Saxifraga cespitosa)

Adaptation: Dense, tufted growth; self-pollination

As its name suggests, this small flowering plant found in rocky tundra habitats grows in dense tussocks that often look like a carpet. Growing in such dense colonies helps lessen the damage from the cold and the wind, plus lessens evaporation on the rocky substrate that has practically no ability to hold water on its own.

The lucky consequence of the packed growing style is the dense ground cover of pretty white flowers during the blooming season.

Additionally, Tufted saxifrage is a self-pollinating species. The pollination doesn’t ever require insect pollinators, as the stamens reach the stigmas, inevitably delivering the pollen to its destination.

Giant Spearmoss (Calliergon giganteum)

Adaptation: nutrient storage, slow growth

The Giant Spearmoss, or Arctic moss, is an aquatic species of moss found growing at the bottom of cold tundra lakes, but also around bogs.

Besides having tiny rootlets instead of any real roots and growing only slightly each year, the Arctic moss has one unlikely cool adaptation which helps it survive the extreme tundra conditions – it can store nutrients gathered during the favourable part of the season, and save them for the following spring when the next growth sprout should occur.

Tundra Plants and Climate Change – The Floral Oracles

Unlike the biodiversity-rich tropical forests and savannas, the tundra was never an overly “popular” ecosystem, and not only culture-wise. Because of its vastness and harsh conditions, it wasn’t always popular to study either.

However, in times of global warming, life in the tundra is becoming increasingly important as an indicator of a significant change.

Scientists are increasingly studying the unique tundra flora and the distribution of its species – because it is an easily visible indicator of changing conditions on the ground. The general trend is that cold-adapted species are moving northwards and are being locally replaced by species more warmth-tolerant.

For example, the collapse of permafrost is regarded as one of the most dangerous tipping points of climate change. As the ever-frozen ground thaws, the revived microbial activity releases tons of greenhouse gasses such as carbon dioxide and methane. This unhinged release would drive global warming beyond any possibility of anthropogenic control and could set the stage for the hothouse earth scenario.

Larger shrubs and trees moving into the tundra is an obvious indicator of thawing permafrost – as the ground gets softer, it can host deeper root systems typical of larger woody plants. This change in plant distribution is highly visible – even by using aerial tools such as airplanes and satellites – meaning that it can be tracked easily with little to no laborious on-foot fieldwork.

Unfortunately, as the world warms, all the uniquely gorgeous tundra plants you’ve read about in this article will have fewer and fewer spaces left to inhabit.

The potential disappearance of the quirky little green heroes of this story tells us that we should be alert. If we lose them, it is not just a loss for the global biodiversity – but a potential loss of the human future and the road to the world that we as a species have never inhabited.

Dwarf Willow (Salix herbacea)

Dwarf Willow (Salix herbacea)