Cephalopoda: Records & Facts About These “Head Footed” Wonders

Cephalopoda Etymology = from ancient Greek kephalē = ‘head’ and pous, pod = ‘foot’ – so “Head footed”

Species Number:– Catalogue of Life: 2019 Annual Checklist = 808, Molluscabase = 823

Fossil Species: Molluscabase = 11 (not including ammonites and belemnites)

Condition of Typical Molluscan Characteristics

- Radula (a rasping “tongue” with chitinous teeth) = Present

- Odontophore = (cartilage that supports the radula) = Absent

- Large Complex Metanephridia = Present

- Broad Muscular Foot = Present (Modified as tentacles)

- Large Digestive Ceca = Present

- Visceral Mass = Present

- Shell = Vestigial and internal (except in Nautilus)

- Habitat = Marine

- Reproduction (Genders) = Dioecious

- Torsion = Absent

Introduction to the Cephalopoda

Cephalopoda is a small but extremely successful class of the phylum Mollusca. They are exclusively marine animals, the only partial exception being the Atlantic Brief Squid (Lolliguncula brevis) which will enter brackish water. Within the world’s oceans they live from the tropics to the poles and from the littoral zone to the abyssal depths. Their species diversity is greatest in tropical waters.

Cephalopods are amazing, graceful in movement and beautiful. Cuttlefish and octopuses are capable of changing colours, most particularly the cuttlefish for whom colour patterns are a form of communication. They have been known to put on incredible displays of rippling changing colours. Peter Godfrey Smith describes this wonderfully in his fascinating book “Other Minds: The Octopus, The Sea, and The Deep Origins of Consciousness“.

Unlike most molluscs cephalopods have bilateral body symmetry (for the most part). They also possess a large, easily recognized head, a set of arms or tentacles which have evolved from the original molluscan foot and the ability to squirt ink. The study of cephalopods is called teuthology, which is a part of malacology.

Octopuses (as you might expect because octo is Latin for eight) have eight arms (rather than legs or tentacles). Squid and Cuttlefish also have eight arms, but they also have two tentacles (which are usually longer, thinner and without suckers) which makes it look as if they have ten arms. Nautili are the most primitive of the cephalopoda, technically they have cirri not arms or tentacles. The number can vary between specimens of the same species but is usually somewhere between 60 and 90.

Basic Biology of the Cephalopoda

All cephalopods are carnivorous predators that hunt using their tentacles to grasp and hold prey. Some possess highly potent toxins to help subdue their prey. The cephalopod mouth and jaw is a beak with which they can bite pieces out of their prey.

Cephalopods can move quickly using jet propulsion of water, however this is energetically expensive and generally only used for short periods of time; for escape and for prey capture. Most octopus can walk across the seafloor, squid and cuttlefish have fins for more gentle locomotion and the two species of nautilus float. Jet propulsion in the two nautilus species is much weaker than in their unshelled cousins.

In contrast to their more numerous gastropod cousins all known cephalopods are dioecious. This means the genders are separate and an individual is either male or female.

Most cephalopods live short lives, two to three years for most species, and have many young. This means they can respond rapidly to changes in the world around them. A paper published in 2016 showed that while fish stocks globally are in decline, dangerously so in many cases, cuttlefish, octopus and squid populations are booming. Which is good news in a way. Two things help this, one, by catching so many fish we are reducing predators and, two, we are also reducing the competition for small food resources.

Origins of the Cephalopoda

The first cephalopods are known from the late Cambrian, however they did not really become successful until the Ordovician period. Early cephalopods are believed to have been primitive nautiloids. Two, now extinct taxa, the Ammonoidea (ammonites) and Belemnoidea (belemnites) were extremely important in their day. They both hunted in the ancient oceans from the Devonian to the end of the Cretaceous when they died off in the same disaster that killed off the dinosaurs. Over 10,000 ammonite species are known to science, spread over hundreds of millions of years.

Some Cephalopod Record Holders

The Largest Cephalopod

There are two traditional ways of measuring the size of animals like cephalopods. One is by weight and the other is by length. These two categories give us different species as the largest living cephalopod. Needless to say there are problems encountered when ascertaining the largest squid. One is the inaccuracy of many older, and non-scientifically verified records. Another is that in preserved specimens the body shrinks and a third is that in living specimens the tentacles are stretchy and can be pulled to be longer than they would be in life.

The Largest Squid

All of the above considered, in the longest category, the winner is the Giant Squid (Architeuthis dux) with an average length of around 11 meters (36 feet). The largest scientifically accepted specimen measured 14 meters including the hunting tentacles.

While the largest cephalopod species is by weight is the Colossal Squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni). The largest specimen ever recorded was caught in the Ross Sea in February 2007, it weighed 450 kg (990 lb). This giant however measured a mere ten meters in total body length, as recorded by The Guiness Book of Records.

Only 677 Giant Squid and 188 Colossal Squid have ever been measured. This, along with the fact the the beak of the Colossal above was considerably smaller than some of the beaks of this species found in the stomachs of Sperm Whales, suggests the species may grow larger than this.

Despite the fears and tales of long dead ocean travelers, cephalopods are not capable of attacking ocean going boats and dragging them down to the depths in honour of Cthulhu. However the largest cephalopods are very powerful creatures, and were you to find yourself in their habitat it would be wise to respect them.

The Largest Octopus

There are two species of Octopus that compete for the world octopus size record. Of these the Giant Pacific Octopus Enteroctopus dofleini is generally considered to be the overall winner. Most adults that are caught weigh around 15 kg, 33 lbs, however individuals that weigh up to 50 kg, 110 lbs are not unusual. Guinness World Records lists the biggest as 272 kg (300 lb) with an arm span of 9.6 m (32 ft). The largest scientifically validated specimen weighed only 71 kg and had a four meter arm span.

The runner up, on records to date, is the Seven-arm Octopus Haliphron atlanticus. A single specimen from the Chatham Rise, New Zealand.in 2002 had a total length of 2.91 meters and a weight of 61 kg. However no other specimens near this size have been caught. The Seven-arm Octopus really has eight arms. However males of this species the unusual habit of keeping their eighth arm, the hectocotylus (a specially modified arm only male octopuses have that is used in egg fertilization) coiled up and hidden in a fold of flesh under its right eye.

The Largest Cuttlefish

The world’s largest cuttlefish species is the aptly named Giant Cuttlefish, Sepia apama. This species can have a body 50 cm (20 in) in length and and can be up to one meter in length including the tentacles and arms. It weighs up to around 10.5 kg (23 lb).

The Largest Nautili

Nautilus pompilius is the largest species of Nautilus alive today. Adults may reach 25.4 cms (10.0 ins) in length. Nautilus macromphalus is the smallest of the six species recognized as of January 2021 with the smallest specimens coming from the Sulu Sea in the Philippines. Specimens of this species have an average diameter of 11.56 cm (4.55 in).

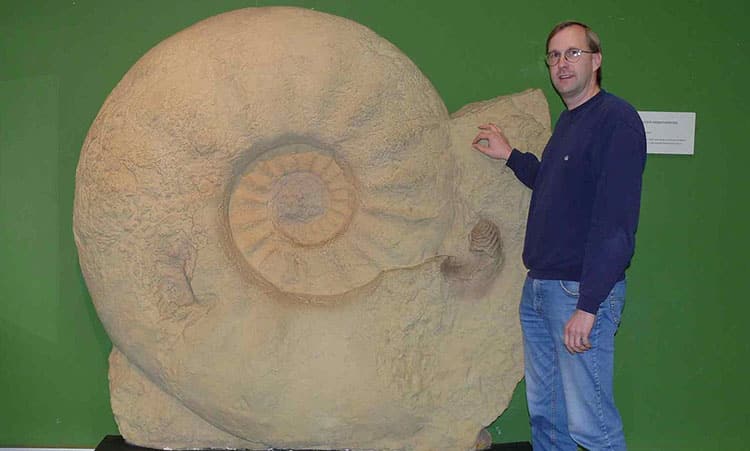

Largest Ammonite and Belemnite

Ammonites and Belemnites are extinct lineages of Cephalopoda. They were dominant predators in the oceans hundreds of millions of years ago. The largest Ammonite is a damaged/incomplete specimen found in Germany in 1895 of a species called Parapuzosia seppenradensis. The remaining shell was 1.95 meters or 6.4 ft across. It is estimated that the complete coiled shell of this antique heavyweight would have measured 2.55 meters, 8.3 ft, across when it was alive.

The largest fossil belemnite ever found was a specimen of Megateuthis gigantea. It is estimated that the living specimen would have been about five meters long including the arms.

The Largest Eye In The World

This record goes to Giant Squid (Architeuthis dux). The largest measured example being from a specimen caught in 1878. This beauty had eyes 40 cm (15.75) ins across. This is not only the largest cephalopod eye, but the largest eye ever recorded or known of for any animal in any habitat on earth, including all known extinct species.

The Smallest Cephalopod

The smallest octopus is the Sri Lankan Octopus (Octopus arborescens) whose average length is 5.1 cms (2.0 ins). Smaller than this is the Agulhas Pygmy Cuttlefish (Sepia typica). A really cute little creature with a body length of just 3.6 cms (1.4 ins).

A popular contender for the the title of smallest cephalopod however is the Southern Pygmy Squid (Xipholeptos notoides). X. notoides is the only species in the cephalopod genus Xipholeptos. Females may reach a length of 2.5 cms, but usually they are smaller than this, less than 2.0 cms in length. Males are even smaller with the largest specimen being 1.58 cms and most being closer to 1 cm in length.

However, even smaller than that, and to the best of my knowledge the smallest Cephalopod in the world and therefore the winner is the Thai Bobtailed Squid Idiosepius thailandicus. The average length of females is a mere 10.4 mm (7.36 – 13.94). The males are even smaller, average length 5.86 mm (4.80 – 7.68). At this size they have no commercial value, even the largest females weigh less that 0.02 grams.

Contentiously Parateuthis tunicata (no common name) is less than 10 mm long (mantle length). However it is only known from two specimens (one adult) collected over 100 years ago. There is some argument over whether it is actually a genuine species. So for now I would say the smallest cephalopoda species in the world is the Thai Bobtailed Squid.

The Fastest Cephalopod.

There is no doubt that squid as a group are the fastest of the cephalopoda. With their ability to jet a stream of water from their mantle, they can reach speeds of 8 m/s (nearly 29 km/hr). This makes them among the fastest aquatic invertebrates in the world. However it is when they fly that they really get fast. In 2011 some Japanese scientist used video recordings of squid flying to estimate that they had a top speed of 11.2 m/s (40.34 km/hr). They didn’t catch any, so the species ID is uncertain, they were likely the Neon Flying Squid Ommastrephes bartramii or possibly The Purple-back Flying Squid Sthenoteuthis oualaniensis.

These flying squid launch themselves from the water using jet propulsion and then unfold the their fins and expand their tentacles/arms to give themselves some aerodynamic capabilities. They can only stay airborne for 20 to 30 meters, but once they return to the water they can take off again very quickly.

The Deepest Living Cephalopoda Species

Despite the common belief that giant squid inhabit the deepest depths of the ocean there are few reports of them deeper than the bathypelagic zone of the ocean 1,000 to 4,000 meters. The deepest scientifically verifiable record of a ‘bigfin squid’ (Family: Magnapinnidae) is an observation at 4735 m in the western Atlantic in the year 2,000.

Unproven reports had suggested that various Dumbo Octopuses could be found much deeper than than this. However it wasn’t until 2019 that this was proven when an unknown Grimpotheuthis specimen was observed and photographed at a depth 6,957 meters (22,825 ft) Java trench in the Indian Ocean – this is the Haddal Zone of the ocean. This report can be seen in a paper published in May 2020.

Identification of species of Grimpotheuthis is not possible from just photographs, so as the specimen observed was not captured it remains unknown which species it was.

The Most Common Cephalopod Species

Generally speaking species with smaller bodies exist at higher populations than animals with larger bodies. Think about sparrows vs eagles, or mice vs buffalo. There are exceptions of course, some smaller species have very limited habitats and there are about the same numbers of cows, goats and sheep on our planet.

However the latter is a result of human modification of the population structure. At our current level of technology it simply isn’t possible to count all the species of creatures that live in the world’s oceans. The best we can do when trying to assess the most common species of squid is to look at the numbers of individual species caught. This will give us some idea as to which species are most populous from among those we humans eat.

Squid are by far the most consumed of all the cephalopods, and as far as we know the most numerous. According to the FAO the two species that contribute most to the average world squid fisheries are the Argentine Shortfin Squid Illex argentinus (511,087 tonnes in 2002) and The Pacific Flying Squid Todarodes pacificus (504,438 tonnes in 2002). Because I. argentinus is the greater amount by weight, and because it is a smaller species that T. pacificus we can assume that it exists in greater populations.

So it is quite likely the The Argentine Shortfin Squid is one of the, maybe even the, most common species of cephalopoda on our planet. However it may not be so every year. Squid like these only live for about two years and their populations can change dramatically year on year as a result of fishing and natural changes in their environment, El nino for example.

The Rarest Cephalopods

The single specimen of Parateuthis tunicata, mentioned above, if it is ever proven to be a valid species, would be a good contender for the prize of rarest cephalopod, however other better known species are also quite rare.

The Most Venomous Cephalopod

Most cephalopods are are venomous to some degree, or so a recent study would indicate. They use their venom to help immobilize prey. However only a couple of species are dangerous to humanity because of the venoms. Two species of Blue-ringed Octopus, from Australia, (Hapalochlaena maculosa and H. lunulata) are the most venomous cephalopods in the world and can be lethal. At least three people have died after being bitten by Blue-ringed Octopuses – they should not be picked up.

The Most Beautiful Cephalopods

It is, as always, impossible to assign an absolute winner to this category. While Cuttlefish are capable of putting on mesmerizing displays of colour, octopuses also have the ability to change their spots. Many octopi are stunningly beautiful when moving about. I believe many people would vote the most versatile octopi as the most beautiful, but which you put at number one must be your own choice.

The Most Unknown Cephalopoda Species

The Larger Pacific Striped Octopus, or Harlequin Octopus wins this title because it has no official scientific name (as of January 2021). This is because it is quite rare and has not been described scientifically. A scientist, Aradio Radaniche, wrote about it in an unpublished report in the 1970s. But because the report was never published it was not known by other researchers, until it was rediscovered in 2013.

The Most Intelligent Cephalopoda Species

Octopuses have been entertaining, intriguing and frustrating aquarium keepers and scientists for decades with their intelligence and problem solving abilities. However it is difficult to actually measure intelligence. This is partly because we humans don’t really understand intelligence even in our own species, let alone in any others.

Separating out an animal’s actions, to distinguish hard wired but complex innate behaviour from the more complex learned or novel behaviour that we think of as intelligence, is extremely difficult. Furthermore, as far as I know scientifically measuring and comparing the intelligence of different species of octopus is something that just hasn’t been done yet.

All that said, tool usage is one of fundamental criteria that we use to define intelligent behaviour. The most profound tool usage observed in the wild is by the Veined Octopus (Amphioctopus marginatus) which has been observed collecting, cleaning out, and carrying for later use, half coconut shells. So until science says otherwise will have to be happy with this answer.

Here I have just barely introduced the concept of intelligence in Cephalopoda, other octopus species and many cuttlefish are also highly intelligent. For a more in depth review of the subject visit our page on Cephalopod Intelligence.

Cephalopod Genetics

The Californian two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculoides), a common laboratory favourite, was the first cephalopod to have its genome sequenced. As a result of the sequencing, scientists noted several things that surprised them.

Firstly the octopuses genome was larger than expected, more than five times larger than other invertebrate genomes with approximately double the number of chromosomes i.e. 28 In total the octopuses genome contained 2.7 billion base pairs and more than 33,000 protein-coding genes. This makes the genome of this small and short lived invertebrate only slightly smaller than the human genome, which has 3-billion-base-pair and 20,000 to 25,000 genes.

Secondly the largely increased aspects of the genome were related to two gene families that had evolved hundreds of novel genes. These genes were all associated with neural development, which may eventually explain the evolution of the octopus’s unique nervous system and brain structure.

A Most Unusual Cephalopoda Specimen

A unique freak of nature, a specimen of the Common Octopus (Octopus vulgaris) was caught in Matoya bay, Japan in 1998. The unusual features of this specimen was that its arms had branched, or divided, in some cases several times. This resulted in it having 96 separate tentacles, or partial tentacles.

Basic Taxonomy of the Cephalopoda

Phylum Mollusca: Class Cephalopoda

Image Credits:- Octopus marginatus by Nhobgood Nick Hobgood, Blue-ringed Octopus by Sylke Rohrlach, Parapuzosia seppenradensis by Gunnar Ries, Sepia apama by Jacob Bridgeman – License – CC BY-SA 3.0; Octopus bimaculoides by Jerry Kirkhart License CC BY 2.0