Family Hymenopodidae Or Jewel Wasps

The hymenopteran family Hymenopodidae, commonly known as jewel wasps or glassy-winged wasps, is a fascinating group of tiny parasitoid wasps. With over 230 described species, hymenopodids display incredibly advanced and diverse host-parasitism strategies to access concealed insect hosts.

They are distributed worldwide but reach peak diversity in tropical regions. In this article, we will provide an overview of hymenopodid taxonomy, morphology, natural history, unique parasitism adaptations, and importance to humans.

Taxonomy

The family Hymenopodidae belongs to the superfamily Ichneumonoidea within the insect order Hymenoptera. They were historically classified as a subfamily (Hymenopodinae) within the larger family Ichneumonidae, which contains most ichneumonoid wasps.

However, phylogenetic analyses of morphological and molecular data in the late 1900s supported elevating them to full family status.

Hymenopodids can be distinguished from other ichneumonids by features including:

- Ovipositor with a single gonapophyseal plate (most ichneumonids have two)

- Small, compact body size, usually less than 5 mm in length

- Fully winged (many ichneumonids are brachypterous)

- Reduced, distinct wing venation patterns

Within Hymenopodidae, there are currently 11 recognized extant genera, with Hymenoepimecis being the most speciose. The family appears most closely related to the diapriid wasps, together forming the sister lineage to the remaining ichneumonoid taxa.

Morphology

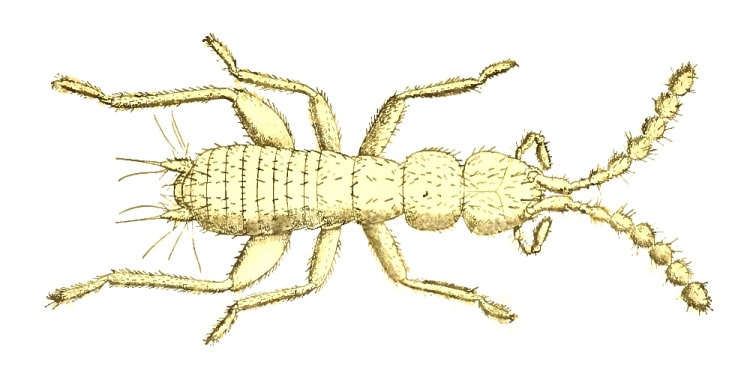

Hymenopodids are very small wasps, ranging from just 1-5 mm in body length. Their bodies are compact and dorsoventrally flattened. The wings are large relative to the body and have reduced venation compared to other ichneumonoid wasps.

The wings are usually clear and glassy, giving rise to the common name “glassy-winged wasps.” However, some species have slightly infuscate or smoky wings.

The ovipositor is exceptionally long given the tiny body sizes of these wasps. It is used to probe through vegetation, wood, and other substrates to access concealed hosts.

Color and Markings

Most hymenopodids have black bodies and legs. Some exhibit yellowish or reddish markings on the legs, metaoma, or antennae. For example, species in the Neotropical genus Pseudodirphya have bright yellow-orange legs and metasomas with black dorsal striping. Hymenoepimecis species sometimes have red-banded antennae or striped legs.

Geographic Distribution

Hymenopodids are found on all major landmasses except Antarctica. They occur in a wide range of habitats from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands and grasslands. However, they are most diverse and abundant in tropical regions, particularly tropical forests of Central and South America, Africa, and Southeast Asia.

Known range extensions into cooler climates are typically limited to the summer months. Overall, there are large gaps in our understanding of this family’s distribution and diversity across much of its range. Further collecting and surveys are needed, especially in the species-rich tropics.

Natural History

Hymenopodid adults can be found visiting flowers and foliage, where they likely feed on nectar and honeydew. However, the larvae are exclusively insect parasitoids. Recorded hosts include a diverse array of concealed insects, such as beetle and fly larvae developing inside stems, fungi, leaf shelters, rotting wood, and ant/termite nests.

The female wasp uses her long ovipositor to probe through substrates like soil, rotting wood, leaf litter or man-made materials to locate potential hosts.

Once a suitable host is found, she drills through the barrier and lays an egg on or near the host. The larva then feeds on and consumes the host as it develops. Eventually, it emerges as an adult wasp that continues the cycle.

Diverse Parasitism Strategies

The hymenopodids employ an incredible diversity of unique adaptations and strategies to gain access to hosts sequestered in well-protected microhabitats. Some of the more fascinating examples include:

Stem borers

Species such as Pseudodirphya and Archihymenoepimecis are egg-larval parasitoids of beetle larvae concealed inside small branches, twigs, or stems. The adult female precisely drills through the plant tissue to deposit eggs directly on the hidden host.

Ant nest invaders

Multiple hymenopodid genera, including Coelichneumon, Euryptera, Hymenopodina and Parvodirphya have evolved to exploit the rich host resources inside ant nests.

They utilize chemical camouflage, mimicry, or morphological adaptations to infiltrate ant colonies undetected and parasitize the brood.

Fungus farming

The genus Hymenoepimecis contains some of the most behaviorally sophisticated hymenopodid parasitoids of spiders. The wasp larvae induce their spider hosts to build special cocoon-like web structures for them to feed on.

Even more remarkably, some species cause the spider to construct an extended silken tube, which the larva infects with a cultivated fungus to eat until it is ready to pupate and consume the host itself.

Acrobatic egg-layers

Species in the genus Archihymenoepimecis have evolved an incredible strategy to parasitize orb-weaver spiders.

The adult wasp precisely mimics the web-building movements of the spider, allowing it to approach close enough to suddenly leap onto the spider’s abdomen and oviposit there. The larvae later consume the spider host.

Parasitoid generalists

In contrast to the specialized strategies above, some hymenopodids are extreme host generalists, able to exploit a wide diversity of concealed hosts.

For example, Pseudocoila and Tropocolus species have been reared from stem-boring coleopteran, lepidopteran, dipteran, AND hymenopteran larvae. This generalist ability allows them to access a variety of microhabitats.

As these examples demonstrate, hymenopodids exhibit exceptionally advanced coevolutionary adaptations for seeking out and parasitizing concealed and protected hosts. Continued study of their natural history will likely uncover even more unique biology.

Defenses Against Parasitoids

The concealed hosts targeted by hymenopodid wasps have evolved a diversity of morphological, physiological, and behavioral adaptations to defend themselves against parasitism.

For example, some beetle larvae that bore inside stems have very thick or woody outer layers that are difficult for the slender ovipositor to penetrate. Hosts may also sequester toxic defensive chemicals in their bodies, making them unpalatable.

Some hosts can detect the vibrations of an ovipositor drilling and may flee the stem or tunnel, abandoning it completely.

Insects in social colonies like ants have cooperative behavioral defenses. Worker ants will fiercely attack intruding wasps, while other workers quickly carry exposed pupae deep into the nest chambers away from danger.

The structure of ant nests themselves, with small chambers and winding tunnels through soil and wood, serves as a physical barrier.

Chemical strategies are also important for social insects. Uniform colony odors help ants recognize foreign invaders. Some bees cover the inner nest cavity with a layer of resin that disguises the scent.

The diversity and ingenuity of host defenses apply intense selective pressure on parasitoids to evolve ever more sophisticated counter-adaptations, fueling the co-evolutionary arms race.

Importance to Humans

Despite their tiny sizes, hymenopodid wasps provide valuable pest control services in many ecosystems by regulating potential pest populations. Some species found in agricultural areas attack stem borers and fungus gnats that can reach damaging levels without natural enemies.

These wasps also have inherent value as components of global biodiversity. Their fascinating natural histories and host-parasitoid relationships provide intriguing study systems for ecology, evolution, and behavior. We have much more to learn from these tiny but sophisticated insects.

Unfortunately, habitat destruction, especially deforestation in tropical regions, threatens many hymenopodid species before they can be discovered. Surveying and describing hymenopodid diversity should be a conservation priority.

Supporting natural history collections and taxonomy in endangered habitats will be vital for ensuring the continued survival and study of these captivating parasitoid wasps.

- Note: some disagreement as to whether Oxypilinae belongs in this family.

Key to subfamilies

1. Pronotum with a markedly toothed edge.

3rd discoidal spine of the anterior femur is markedly lengthened.

subfam. Oxypilinae

Pronotum with a smooth or at most slightly beaded edge.

3rd discoidal spine of the anterior femur of normal length.

2. Frontal sclerite may have lateral tubercles, or slightly raised lateral strips, but does not have raised lateral wing-shaped keels; the central portion is not depressed;

the dorsal edge never with two small teeth.

Eyes within outline of head.

subfam. Acromantinae

Frontal sclerite with raised lateral wing-shaped keels; the central portion depressed; the dorsal edge with two small teeth.

Eyes separated from vertex by a deep ridge; bulging outside circumference of head.

subfam. Hymenopodinae

Subfamily Oxypilinae

Key to genera

1. Pronotum as long as anterior coxa.

genus Pseudoxypilus

Pronotum shorter than anterior coxa.

2. Prozone of pronotum with two conical tubercles.

Prozone of pronotum with four conical tubercles.

3. Metazone of pronotum with four tubercles.

genus Pachymantis

synonym Echinomastoharpax Werner

Metazone of pronotum with two tubercles.

genus Ceratomantis

4. Posterior femora with three tooth-shaped lobes.

genus Junodia

Posterior femora smooth.

5. Distal external spines of anterior femora equal in length to proximal spines.

Female apterous.

genus Oxypilus

synonym Anoxypilus G-Tos

Distal external spines of anterior femora shorter than proximal spines.

Female winged.

genus Euoxypilus

Back to key to Hymenopodidae

Subfamily Acromantinae

Key to tribes

1. Front femora with four outer spines.

tribe Acromantini

Front femora with 5-7 outer spines.

2. Front femora with 4 discoidal spines.

tribe Epaphroditini

Front femora with 3 discoidal spines.

tribe Acontistini

Tribe Acromantini

Key to genera

1. Eyes rounded, bulging; not cone shaped.

Eyes distinctly cone shaped.

2. Pronotum slim, distinctly longer than anterior coxa; well-defined supra-coxal bulge.

Pronotum squat, shorter or at most only as long as anterior coxa; poorly defined supra-coxal bulge.

3. Pronotal shield without tubercles.

Pronotal shield with cone-shaped tubercles.

4. Middle and posterior femora without lobes.

genus Anaxarcha

synonym Anaxandra Kirby

Middle and posterior femora with preapical lobes.

5. Internal apical lobes of anterior coxa adjacent.

Internal apical lobes of anterior coxa separated.

6. Vertex without tubercle above ocelli.

Vertex with cone-shaped tubercle above ocelli.

7. Elytra with finely meshed veins.

genus Heliomantis

synonyms ? Paraspilota Bolivar, Deiroharpax Werner

Elytra with widely spaced veins.

genus Oligomantis

8. Middle and posterior femora with only a single subapical lobe.

Elytra with widely spaced veins.

genus Rhomantis

Middle and posterior femora with 3 lobes.

Elytra with finely meshed veins.

genus Psychomantis

9. Anterior femora with a projecting three-cornered lobe on dorsal aspect.

genus Citharomantis

Anterior femora with dorsal border more or less bent, lamelliform, but without a

lobe.

10. Dorsal aspect of frontal sclerite blunt.

genus Neacromantis

Dorsal aspect of frontal sclerite three-cornered.

11. Vertex with at most a small tubercle above the ocelli.

genus Acromantis

Vertex with cone-shaped projection.

genus Anasigerpes

12. Anterior coxa strongly armed.

genus Ephippiomantis

Anterior coxa almost unarmed.

genus Catasigerpes

synonyms Sigerpes W-Mason (non Sigerpes Germar), Oxypiloidea Schulthess-Schindler

13. Anterior femora normal, not dilated.

genus Odontomantis

synonyms Antissa stål, Euantissa G-Tos

Anterior femora dilated with lamellae.

14

14. Pronotal disk without tubercles

genus Hestiasula

synonyms Hestias Saussure, Ephestiasula G-Tos, Catestiasula G-Tos

Pronotal disk with tubercles

genus Chrysomantis

synonym Uvaromantis (Ragge & Roy 1967, p.637)

15. Pronotum slim, longer than anterior coxa.

genus Metacromantis

Pronotum squat, shorter than anterior coxa.

16

16. Pronotal disk without tubercles.

genus Otomantis

synonym Acanthomantis Saussure & Zehntner

Pronotal disk with tubercles.

genus Anoplosigerpes

- Included by Giglio-Tos but not Beier: Ambivia, Danuriella, Phyllothelys (? Phyllothelis, -> own subfamily)

1. Eyes round. Posterior tibia with large lobes.

genus Phyllocrania

Eyes cone shaped. Posterior tibia without lobes.

2

2. Anterior femora with 7 external spines.

genus Metilia

synonym Acanthogaster Werner

Anterior femora with 5-6 external spines.

3

3. Anterior femora with 6 external spines. Pronotum not expanded with lateral lobes.

4

Anterior femora with 5 external spines. Pronotum expanded with lateral lobes.

5

4. Vertex with bifid projection above ocelli.

genus Pseudacanthops

synonym Paracanthops Saussure

Vertex without projection.

genus Acanthops

synonyms Decimia Stål (? original source for this synonymisation), Plesiacanthops Chopard

5. Hind femora with dorsal preapical lobe.

genus Antemna

Hind femora without dorsal preapical lobe.

genus Epaphrodita

- Included by Giglio-Tos but not Beier: Parablepharis

- Transferred here by Beier Amphecostephanus Rehn

1. Mediastinal vein of costal area of elytra without distinct oblique branches.

External spines of anterior tibia closely packed, layered.

2

Mediastinal vein of costal area of elytra with distinct oblique branches.

External spines of anterior tibia straight, spaced.

genus Tithrone

2. Pronotum rather rounded. Wings clear or opaque, but not violet coloured.

genus Acontista

synonyms Acontistes Burmeister (non Acontistes Sundewall), Acontiothespis Hebard

Pronotum thin. Wings for the most part smoky brown with a stronger or weaker violet iridescence.

genus Acontistella

- Included by Giglio-Tos (Beier has it as genus incerate sedis): Astollia Kirby

Key to genera

1. Pronotum with expanded supracoxal lateral lobes, the whole as a result cross-shaped.

2

Pronotum without markedly expanded supracoxal lateral lobes, the whole more or less oval, not cross-shaped.

6

2. Anterior femora with three discoidal spines.

3

Anterior femora with four discoidal spines.

4

3. External marginal spines of anterior femora markedly bulbous at their bases.

genus Pseudocreobotra

synonym Pseudocreobrotra Saussure

External marginal spines of anterior femora plain, not markedly bulbous at their bases.

genus Theopropus

4. Eyes pointed, cone shaped.

genus Harpagomantis

synonyms Harpax Serville, Australomantis Rehn

Eyes rounded.

5

5. Prozone of pronotum with obtuse tubercles.

Anterior femora stocky.

genus Anabomistria

Prozone of pronotum with pointed tubercles.

Anterior femora slim.

genus Chlidonoptera

synonym Bomistria Saussure

6. Anterior femora with 3 discoidal and 5 outer spines.

genus Callibia

synonym Anastira Gerstäcker

Anterior femora with 4 discoidal and 4 outer spines.

7

7. Eyes round.

8

Eyes cone shaped.

10

8. Middle and posterior femora without lobes.

Frontal sclerite with a central keel.

genus Chloroharpax

Middle and posterior femora with lobes.

Frontal sclerite smooth, without central keel.

9

9. Vertex without protuberance.

genus Propanurgica

Vertex with protuberance above ocelli.

genus Panurgica

synonym Mystipola Saussure

10. Pronotum slim, longer than anterior coxa.

genus Galinthias

Pronotum squat, shorter than anterior coxa.

11

11. Middle and posterior femora with large lobes, occupying at least half the length of the femur.

Middle and posterior femora with small preapical lobes only.

13

12. Vertex without protuberance. Eyes bluntly conical.

genus Parymenopus

synonym Parhymenopus G-Tos

Vertex with protuberance. Eyes sharply conical.

genus Hymenopus

synonym Hymenopa Serville

13. Tubercles above ocelli pointed.

genus Pseudoharpax

synonym Pseudoarpax Stål

Tubercles above ocelli blunt.

14

14. Eyes with small terminal tubercle.

genus Helvia

Eyes without terminal tubercle.

genus Creobroter

synonyms Creobotra Saussure, Creoboter Stål, Creobrotra Saussure