Gastropod Reproduction 101 (The Whole Truth)

Introduction to Gastropod Reproduction

Gastropod reproduction involves strategies that are as diverse and as fascinating as everything else about this amazing group of animals. In nearly all gastropods reproduction involves the exchange of genetic material. In terrestrial, and most other species reproduction involves an amount of courting and then an exchange of male genetic material through internal fertilization of both individuals at the same time. Internal fertilization is the norm for gastropods, the most notable exceptions are the limpets in whom fertilization is external.

Fertilization involves the exchange of male reproductive cells by means of a penis. The gastropod penis is an extendable and flexible organ. Usually it delivers sperm to the partner’s body near the tail, but the exchange of sperm can also occur at the tips of the two penises. This is the case in terrestrial slugs.

In some species, the penis can be far longer than the individual animal. The European slug Limax redii has a body length of about 13 to 15 cms but a penis length of 75 cms during copulation. This species mates by meeting in a tree. The two partners entwine their bodies and let their penises hang down and also entwine. A habit which makes it easy for scientists to measure them.

Snails have poor vision and no apparent hearing. It is not surprising then that they have developed a suite of chemical hormones that they use to signal to each other that they are ready and willing to mate. Scientists have given these hormones names like “attractin” “enticin” and “seducin” (Painter et. al. 2004).

Mated snails, store the sperm they receive in a special sperm storage organ called a “spermathecae”. Individual snails usually mate more than once and the stored sperm is mixed. When sperm are used to fertilize ova, it is a random choice as to which partner’s sperm ends up being used. This mean the young hatching from a single batch of eggs usually have mixed parentage, at least in terms of the male partner.

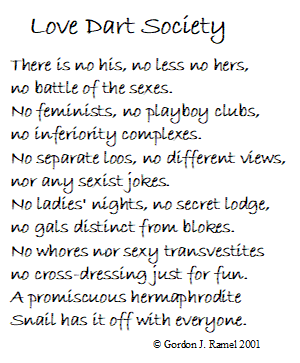

Those Infamous Love Darts

Little is understood of their ecological function, but in at least one species they seem to stimulate sperm retention in the receiver. Where they do occur they can be used in different ways. Most snails use just one dart and it is usually used just the one time. However the Japanese species Euhadra subnimbosa may stab its partner over 3,000 times during copulation.

Some Gastropod Reproduction Vocabulary

- Dioecious = Possessing to separate genders, i.e. individuals are either male or female throughout their whole life.

- Gonochoristic = Is another term for Dioecious.

- Hermaphroditic = Being both male and female at some time during life.

- Parthengenetic = Reproduction without a partner a single individual produces young on its own. There are several ways this can occur.

- Simultaneous Hermaphroditism = Having both male and female reproductive organs at the same time.

- Sequential Hermaphroditism = Being first one gender and later changing to the other gender.

- Protandry = Hermaphroditism where the individual is male first and later becomes female.

- Protogyny = Hermaphroditism where the individual is female first and later becomes male.

- Viviparity = Producing offspring that develop as embryos within, and derive nourishment from, the mother’s body.

- Ovoviviparity = Producing eggs that are retained within the mother’s body and hatch there.

- Oviparity = Producing eggs that are laid and which hatch outside the mother’s body.

- Iteroparity = Able to produce young on two or more successive occasions before dying.

- Semelparity = Able to produce only a single batch of young, after which the female dies.

Precourtship and Courting Behaviour in Gastropods

Courtship and the courting of partners before mating is little studied in the majority of gastropod species. As most mobile gastropods lead solitary lives, the first step is simply finding an another adult member of your species. This can be achieved by following chemical cues and slime trails in terrestrial species.

Once two reproductively active adults have met, in the breeding season for those species which have one, they begin to get to know one another. For many of those terrestrial snails that actually have love darts, stabbing each other with these darts are part of the courtship behaviour.

Heike Reise defines ‘precourtship’ in terrestrial slugs as “the partners encounter and investigate each other” and ‘courtship’ as beginning when both partners have their sarcobelum (penises) protruded from the genital opening and assume a position with their genital pores facing each other, forming a circle or yin-yang configuration. However he admits there is great variety between species, in some species there may be a time lag between when one individual everts its penis and when the other partner reciprocates. Also in some species the penis may be withdrawn by one or both partners during courtship.

Reise studied slugs in the genus Derocerus and amassed a great deal of information about them. He reports that courtship in these slugs involves lots of physical contact, the rubbing and entwining of bodies, and touching with the tentacles and mouth of each other.

Courtship in the terrestrial slugs of the genus Deroceras is a surprisingly long affair. For Derocerus gorgonium he reports 95-276 minutes for the precourtship phase, 145-434 minutes for the actual courtship phase and a mere 18-25 seconds for the final copulation. The courtship phase is usually the longest phase and copulation usually much shorter and measured in seconds rather than minutes. However, as always in Nature, there are exceptions and for Derocerus sturanyi he reports: Precourtship 15-120 min; Courtship 26-169 minutes; Copulation 60-169 minutes.

Gender and Sexuality in Gastropod Reproduction

Introduction

Gastropods are an extremely diverse group in respect of sexual systems and reproductive strategies. They can be dioecious with separate sexes or hermaphroditic. Hermaphroditism can be either simultaneous or sequential. Sequential hermaphroditism can be either protandric or protogynic.

The majority of gastropods are either dioecious or simultaneous hermaphrodites. Simultaneous hermaphrodism dominates in terrestrial environments (all known pulmonate molluscs are hermaphrodites) and dioecism in marine environments. But there is much variation, the opisothbranchs, including the beautiful Nudibranchs, are nearly all simultaneous hermaphrodites but also exclusively marine.

Hermaphroditism occurs in 99.5 of the Heterobranchia, but only in 3% of the Prosobranchia (taxonomy as of 1993).

Sequential Hermaphrodites

Sequential hermaphroditism is the reproductive strategy of first being one gender and then later changing to the other. Evolutionary biologists explain that the choice of which gender to be first is governed by the “size-advantage hypothesis”.

According to the size-advantage hypothesis, gender change is favored by natural selection where reproductive success increases more quickly with size (or age) for one gender compared to the other. The theory predicts that gender change occurs at the size (or age) where the reproductive success curves of males and females intersect. In other words the animals have evolved to maximize the number of young they can produce, which live and go on to reproduce themselves.

However this theory is not water tight, in many gastropods social pressure is known to have a strong, even a controlling effect on the occurrence of gender transition in some species. Basically, the presence of females inhibits the gender change in protandrous males. Coralliophila neritoidea is a marine snail from the Indo-Pacific region in which field studies have proven that males delay gender change in the presence of females.

Protogyny

Protogyny is much less common in the animal kingdom than protandry. This is because the advantages for reproductive success with increasing size are greater for females than males. Because these strategies are sequential, the animal will be smaller as whatever gender it is first and larger as the second gender. All this means it is ecologically better to be a smaller male first and a larger female later than the other way around.

There are no protogynous gastropods that I know of. But it is known to occur in nature, especially in animals where there is a constant increase in size with age and where a dominant large male keeps, and fights for, a harem of females. Smaller males cannot protect their harem from larger males so it is better to be female (if you are going to be sequentially hermaphroditic) while you are small.

Protandry

Protandry is the form that all know sequential hermaphrodites follow within the class gastropoda. Fundamentally sperm are biologically cheaper to produce than ova. However, ova are more likely to become new individuals than sperm. This is especially true of brooding species in which females can ensure that all their ova mature and hatch. Once a male has released his sperm, especially in species with external fertilization, he has no guarantees that these will result in any hatched young at all.

The Slipper Limpet, also known as the Boat Shell (Crepidula fornicata) is a common, and invasive, protandrous species of gastropod. This species is well know for forming stacks. These stacks are hierarchically organized according to size with the biggest at the bottom and the smallest individuals at the top. The largest individuals, those at the bottom, are female; and the smaller, those at the top, are the males.

As the largest females at the bottom die, the biggest of the males change gender to become female. In this way the balance of reproductive genders is maintained. The gregarious habit that stacking represents is beneficial for the males whose reproductive success is increased as the size of the stack increases. Scientific research published in 2006 shows that 92% of the reproductive crosses occurring within a stack occurred between individuals located in the same stack.

Simultaneous Hermaphrodites

In simultaneous hermaphrodites mating can be reciprocal or unilateral. Reciprocal mating is common among slugs, whose bodies are flexible and unencumbered by a shell. In their form of mating, both slugs act as males and females at the same time. This manner of mating requires that the pair of genitalia be exactly opposed prior to copulation, all gastropods rely heavily on chemoreception and contact sensation to facilitate mating. There is usually an exchange of sperm, but one-way sperm transfer is known to occur.

In unilateral mating, each individual has a defined gender role during the mating act: one performs as the male and donates sperm while the other performs as the female and receives the sperm. It is usual amongst terrestrial gastropods for the individuals to switch roles after sperm transfer, for a second round of mating – ensuring both individuals have a chance to produce fertilized young. This is not the rule for terrestrial slugs however, who can mutually exchange sperm at a single mating.

In slugs the penis has evolved into a strange looking and highly expandable organ. Mating slugs entwine their bodies and a their penises, sperm exchange occurs through the tip of the penis.

Some simultaneous hermaphrodites, in which the male and female organs are on opposite sides of the body, will form chains of reproduction. These are sometimes called ‘daisy chains’. In these chains the individuals at either end are operating as male (one end) and female (other end), but all the other individuals in the chain are functioning as both reproductive male and females at the same time. Aplysia californica is an example of a species that does this.

In the hermaphroditic freshwater snail Bulinus truncatus, two sexual morphs occur stably through the population. Euphallic individuals = regular hermaphrodites and aphallic individuals = individuals without a male copulatory organ. Both aphallic and euphallic individuals are able to reproduce by both selfing and by outcrossing, however when outcrossing aphallic individuals can only play the female role.

Imposex Gastropods and Tributyltin

Tributyltin (TBT), was an extensively used biocide in antifouling (AF) paints from the late 1960s until it was banned globally in 2008. Because it was painted onto the hulls of ships, it soon became a serious pollutant of marine ecosystems. One of the more notable results of TBT pollution was the creation of Imposex individuals in some common gastropods.

Imposex is defined as the superimposition of male sexual characteristics (including a vas deferens and/or a penis) onto the genital tracts of females; which, in severe cases in some species, led to female sterility. Sterilizing the females of a species can quickly lead to its extinction if it isn’t controlled. One of the most sensitive species to TBT induced imposexuality is the dog whelk Nucella lapillus. This species has been used to monitor TBT pollution in marine waters for decades.

During the worst decades of TBT pollution, Dog Whelks disappeared from some European coastal areas. It was found that in the areas where the species survived a percentage of the population suffered from Dumpton Syndrome (DS). Dumpton Syndrome is named after the place where it was first observed, Dumpton Gap. Dumpton Syndrome is a a male genital defect that causes underdevelopment of the male genital tract. Males affected by DS show a smaller (or a complete lack of) penis, incomplete formation of the vas deferens and a split prostate.

This defect, which can cause male sterility in severe cases, is an advantage in TBT polluted areas because it causes a lower degree of masculinization in females. DS-affected females were therefore not sterilized and could reproduce with non-DS males, whose offspring inherited the DS character by Mendelian transfer. Thus by a twist of fate the species survived.

A Few Final Twists

A further complication occurs when we examine the timing of reaching sexual maturity in simultaneous hermaphrodites. It is quite common for individuals of such species to mature as males before they reach maturity as females. This means that for a short period of time they are reproductively males only. Then, a little time later, they are reproductively both male and female.

Finally in some species, towards the end of their reproductive life, the male reproductive functionality can be lost. Meaning the individual become functionally a dioecious female. This is not the same as distinct sex change however, because for most of their reproductive life they have been hermaphroditic.

A very unusual situation in gastropods is where individuals switch gender more than once. This two-way sex change, or reverse sequential hermaphroditism, has been observed in the endangered limpet Patella ferruginea from the Chafarinas Islands.

Apophallation

Apophallation is the rather grisly behaviour that is occasionally found in some species of slugs, particularly in the genus Ariolimax, in which the penis is amputated.

Penis amputation takes time and involves one or both slugs is chewing off using the penis using the radula. As far as is known, a replacement penis does not grow back. This means that after such a mating the unlucky individual is no longer able to mate as a male and can only reproduce in the future as a female. The severed penis is usually eaten by the mating partner.

Apophallation is a last resort rather than normal behaviour. The reasons why the penis becomes stuck is unclear, but it may be that the partner’s female parts become locked onto the penis and are unable to release it. Apophallation may bring reproductive benefits to the amputator because it prevents the amputee from mating again in the near future. This would improve the amputee’s chances of being the father of this season’s eggs.

Autoapophallation (self-amputation) occurs occasionally in another species of slug Deroceras laeve. As far as is known, as in Ariolimax species, the penis does not grow back – meaning mated individuals are effectively female for the rest of their life.

Parthogenesis and Self Fertilization in Gastropods

Self fertilization occurs when a hermaphroditic species uses its own sperm to fertilize its own ova. Parthenogenesis occurs when a dioecious female produces young without the ova being fertilized. There are several biological pathways to parthenogenesis and in some cases all the offspring are female.

Self Fertilisation is not all that rare in gastropods, J. Heller lists 28 genera of gastropods in which self fertilization occurs and 14 in which parthenogenesis occurs. In comparison hermaphroditism is known from 2,141 genera (as of 1993) including 100% of the pulmonata, 99% of the Opisthobranchia, 91% of Heterostropha.

Alinda biplicata is an example of viviparous land snail from Central Europe. An adult will give birth to between 1 and 8 young at a time. A healthy adult will give birth to young snails several times a year (in the right habitat) and individuals can live for up to four years, so they are an iteroparous species. Alinda biplicata is a simultaneously hermaphroditic species which is capable of self fertilization. However self fertilization results in less young being produced than fertilization by another individual.

Campeloma decisum is a freshwater pulmonate snail from the USA. It is an interesting because it is a parthenogenetic species and because science understands, to some extent, how it came to be parthenogenetic. The species has a limited distribution and is parasitized by a digenetic trematode, Leucochloridiomorpha constantiae.

A side effect of the parasitism is that males become functionally sterile. This is called parasitic castration. Evolving the ability to reproduce parthenogenetically the snail has survived – and inadvertently kept its parasite alive too.

Gastropods store sperm from their partners and it may remain functional for several years. During this time the adult will likely mate with other individuals and collect sperm from them also. Thus the stored sperm that is later used to fertilize ova often comes from more than one partner. This means that the individuals hatching from eggs produced at a single reproductive event quite likely do not all share the same father.

Gastropod Eggs

There is great diversity among gastropods in how they lay their eggs. Most species are oviparous, meaning that fertilized eggs are laid or deposited at a stage where very little internal growth has occurred. Land snails usually deposit their eggs in a primitive kind of nest in moist, loose soil. My personal experience is that they like a mature compost. Sea slugs lay their eggs in long gelatinous strings or ribbons. Some species like Clanculus berthelotii deposit their eggs into grooves on their own shell (see the gastropod shell page) and cover them with mucous.

Aquatic gastropods generally deposit their eggs in gelatinous masses that are attached to a hard surface. Opisthobranchs often lay a very large numbers of eggs. For example, a single specimen of Aplysia californica was observed depositing one egg mass that contained 140,000 eggs. Terrestrial snails and fresh water species usually lay a much small numbers of eggs. For terrestrial species the numbers vary from less than 10 at one time, to over 100 (in difficult years some species may only deposit one or two eggs at a time). Freshwater species usually lay larger numbers; 50 to 150 for Lymnaea stagnalis, 50 to 200 for Pomacea urceus, 200 to 600 for Pomacea canaliculata and up to 2,000 for Pomacea maculata.

The figures above are for the number of eggs in a single egg mass, however during the spawning season an individual may lay eggs several, or even many, times. Aplysia californica will typically lay eggs at intervals of 1 or 2 days. Lymnaea stagnalis lays it eggs about once a week during the breeding season and land snails normally lay eggs only two or three times per season. As a result of this an individual of Aplysia californica can lay as many 150,000 eggs in a season.

Many marine species produce egg capsules, these can contain anything from 5 or 6 to about one thousand developing eggs. The shape and design of these egg capsules varies greatly between species and they are often quite beautiful. The egg capsules supply additional protection for the eggs while they are developing. Egg capsules offer the eggs within protection against predation, desiccation, osmotic shock, ultra-violet light and bacterial attack – all of which can kill unprotected eggs.

Some species attach their egg capsules to the substrate and have nothing further to do with them, others attach their capsules to either their own shells, or the shells of other molluscs. Conversely some species, especially the sedentary Slipper Limpets in the genus Crepidula attach their capsules to the substrate within the shell cavity of the female, thus offering them some additional protection during their development.

Finally, as an exception to this rule concerning attachment of capsules, there is the species Adelomelon brasiliana which produces egg capsules that are large in relationship to the number of young within and which are pelagic. This has results in them getting washed ashore during storms where they can be preyed upon by shore birds and photographed and displayed on Facebook.

To find out what happens after the eggs have hatched, visit our page on the Gastropod Life Cycle.

A Final Comment on Pollution

The genius of Goethe was never so present as when he wrote The Sorcerer’s Apprentice as a warning to mankind. A warning most of us, including our governments, have not learned or understood yet. Personally I would liken our situation more to that of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice’s child, because of the childlike way we play with forces we do not even begin to understand. Driven, as we are, by greed, egotism and hubris to turn every new scientific discovery into a global disaster.

Endocrine Systems

The endocrine system involves chemical messengers that are secreted to coordinate various mechanisms and physiological processes of a multicellular organism. This system allows the organism to react appropriately to numerous external (environmental) and internal (physiological) signals. Every multicellular species has its own complex, but strangely related, endocrine system. Related so that chemicals that affect the mammalian endocrine system can also trigger responses from the endocrine systems of other organisms, including fish and molluscs.

Gastropods are numerous in the oceans that surround us, and in fresh water habitats. They are, as a group, easy to obtain and study – and as such they warn us of the dangers of pouring chemicals into aquatic habitats.

As well as the chemical induced physiological changes mentioned above in the paragraph on Imposex, gastropods join other molluscs, fish and crustaceans in having their endocrine, and subsequently their physiology, negatively impacted by the ever increasing flood of hormones and other chemicals flushed into the oceans from the agricultural industry. This is because the endocrine system uses chemicals to communicate; therefore the receptors that work as part of the endocrine system are chemical receptors, and are therefore vulnerable to corruption by chemical pollutants.

Chemically Triggered Dysfunction

Both bisphenol A (BPA) and octylphenol (OP) are known to interfere with the normal reproduction of the fresh water gastropod Colombian Ramshorn Apple Snail (Marisa cornuarietis).

The effect in this case is to cause hyperactivity of the reproductive system resulting in the accumulation of egg masses in the female pallial glands (albumen and capsule glands) which in turn leads to the rupture of the oviduct in females, ultimately resulting in death. Other chemicals implicated in dysfunctionally increased egg production include nonylphenol (NP) and ethynyl estradiol (EE2).

Among the many other pollution induced physiological changes that have been observed the most common are; delayed oogenesis or spermatogenesis, tubule necrosis, inflammatory reaction (infiltration of phagocytic haemocytes), conjunctive tissues proliferation and ovotestis in gonochoristic molluscs, including gastropods

It All Comes Home

Since the inception of global industrialization, steroidal estrogens have become an emerging and serious concern. Worldwide, steroid estrogens including estrone, estradiol and estriol, pose serious threats to soil, plants, water resources and humans. Indeed, estrogens have gained notable attention in recent years, due to their rapidly increasing concentrations in soil and water all over the world.

Concern has been expressed by scientists for decades now regarding the entry of estrogens into the human food chain which in turn relates to how plants take up and metabolize estrogens. Estrogens at pollutant levels have been linked with breast cancer in women and prostate cancer in men.

Well that’s all for now. To continue learning about gastropods why not visit our Gastropod Life Cycle Page.

Image Credits:- Alinda biplicata by Bj.schoenmakers license CC0 1.0; Cover image = Mating Snails in Mozambique by Ton Rulkens, Common Slipper Shells (Crepidula fornicata) by Andrew C, Mating Nembrotha rutilans by Nick Hobgood – license CC BY-SA 2.0; Mating snails pulled apart by Carla Isabel Ribeiro, Mating Slugs by Spleines, Mating Marine Snailsby Madhumay – license CC BY-SA 3.0; Dog Whelk by Ryan Hodnett, Patella ferruginea by Mariachiara Chiantore – license CC BY-SA 4.0