Cicadas 101: The Singing, Musical World Of Family Cicadidae

The word Cicadas derives directly from the Latin Cicada (in Greek they are called Tettix, or Tzitzi).

Insects were thought by some people to be quite similar to mankind… and it was with this thought in mind that J.G.Myers in his lovely book “Insect Singers” wrote the following:

“It will not therefore surprise one to find the greatest musical artists of the insect world among its deepest drinkers.”

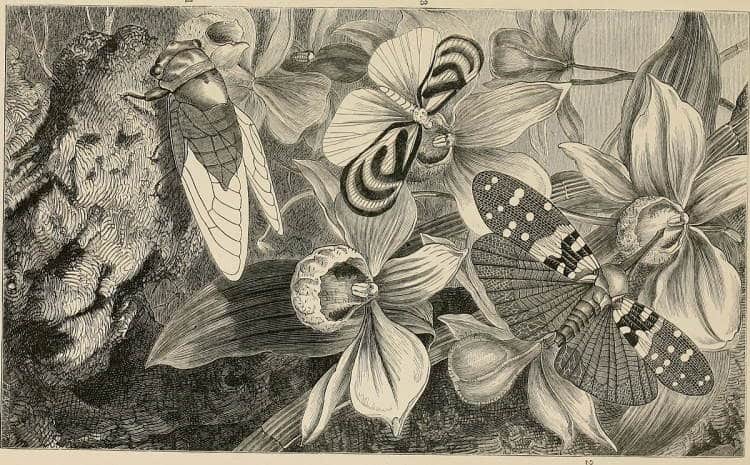

Their sudden appearance in the hottest season of the year, their mysterious feeding habits, and above all their striking musical performances have attracted mankind’s attention to the Cicadas for thousands of years.

Cicadas are members of the Hemiptera, then the Homoptera (the Homoptera is often considered an order in its rite these days, but in some books, you will find it designated as a suborder of the Hemiptera). They are then members of the superfamily Cicadoidea, and the Family Cicadidae (or in the case of two unusual Australian species Family Tettigarctidae).

There are about 1,500 species of Cicada in the world; some of the largest are in the genera Pomponia and Tacua. There are 202 species in Australia, compared with about 100 species in the Palaearctic – and only one species in the UK.

The British species is Melampsalta montana (Cicadetta) which is widespread outside of the UK and occurs up to 61o north. It seems to prefer pines, though old larval skins exuviae have been found on grass stems and occasionally Bracken Pteridium aquilonia. Cicadas are mainly warm-temperate to tropical in habitat.

Generally speaking, cicadas have life cycles that last from one to several years. Most of this time is spent as a nymph under the ground, feeding on the xylem fluids of plants by piercing their roots and sucking out the fluids. Some species take a very long time to develop; the periodical cicadas of the genus Magicicada of North America are well known because some of them have a 17-year life cycle.

You may use the links below to skip directly to the relevant section of this page:

There are 3 species of periodical cicada, each of which has two forms: a 17-year form and a 13-year form; they are M. septendecim, M. septendecula, and M. cassini.

Some authorities claim that the 13-year form of each species should be a species in its rite; in this case, they would be named; M. tredecim, M. tredecassini , and M. tredecula. Of the three species (called Decim, Cassini, and Decula for short) Decim is the most common in the north of their range; Decula is rare all over; and Cassini is most common in the Mississippi valley.

In addition to this, the 13-year broods tend to be centrally placed within the Cicadas distributional range and the 17-year forms are found more to the North, East, and West. It is possible for populations to switch between the 13 and 17-year lifecycles for various reasons.

Periodical Cicada populations can be tracked, depending on their emergence times and it is possible for populations to be reproductively isolated because of their different emergence years. Populations are designated broods, depending on the timing of their cycle; there are therefore seventeen 17-year broods and thirteen 13-year broods. The 17-year broods are named in Roman numerals I – XVII and the 13-year brood XVIII – XXX.

Theoretically, therefore, there are 30 broods – but no emergencies are known for some of the years. Presently there are 12 known broods for the 17-year cicadas and only 3 known broods for the 13-year cicadas; meaning there are only 15 observed emergences.

An interesting fact arising from all this is that the respective 17 and 13-year broods of any one species only overlap once every 221 years.

I.e. broods V and XXII emerged synchronously in 1897 and will not do so again until 2118.

Periodical cicadas tend to emerge between late April and early June. Both males and females congregate in choruses for the first couple of weeks, to sing and mate; the females disperse to lay their eggs. The eggs take 6-8 weeks to hatch and, like all cicadas, head straight for the soil.

It has been estimated that in some cases 98% of the hatching nymphs die in the first 2 years of life.

Unlike most Homopterans, Cicadas tend to be both facing in the same direction during copulation. Copulation has not often been observed in many species. Female Melampsalta leptomera a New Zealand grass-laying species has been observed to mate successively between egg-laying bouts. Copulation takes about 1 hour in Cicadatra querula.

Cicada eggs are long, thin cylinders – slightly pointed at one end. One female may lay 400–600 eggs in the periodical cicadas and 500-600 in the Tibicen plebia.

All known cicada eggs are inserted into plant material. Eggs are laid into what are called ‘eggnests’, each of which contains a small number of eggs and is cut into the plant material by the female using her ovipositor. The eggs turn salmon pink prior to hatching, and the nymphs are normally a similar colour on hatching.

Females of Magicicada septendecim can be observed testing the tree they are on for suitability, before laying eggs. First, she grasps the twig with her forelegs, measuring its size. Twigs that are not between 3mm and 11mm in diametre are generally rejected.

Secondly, by dragging her proboscis over the twig and perhaps inserting it – she is tasting the tree for secondary compounds such as those found in Pines or Black Cherry (which will normally result in the tree being rejected). Thirdly, by probing with her ovipositor, she is testing how hard the wood is.

Thus, by testing the tree and by observing the presence of other ovipositing females, a female makes her decision whether or not to lay.

The eggs of cicadas are longer than broad and oval. The females have a saw-like ovipositor, with which they dig a hole/crevice in some plant material. Normally, this is the plant species that the larvae will be able to feed on, or a plant near to the larval food plant.

The female takes some time to create her nest; in areas where cicada populations are high, partially constructed and abandoned nests may be found in various stages of construction.

Females lay several eggs per nest and some species line the nest with a sort of foam – which hardens and gives added protection to the eggs. In Magicicada septendecim, which uses several host plants but prefers Box Elder, the female constructs the nest with two chambers.

One chamber is made first and filled with eggs and then the second chamber is made and also filled with eggs. The result appears to be a 2-sided chamber, filled with eggs. However, if the female is disturbed during egg laying she will leave the nest partially finished. There is some evidence to suggest that females will abandon nest attempts on some tree species more regularly than on others, but the causes for this are not well understood.

Cicada nymphs are all very similar; the head is more conically produced (sticks out forwards more) than those of the adults and they possess a strong rostrum. The antennae are also longer and stouter than in the adults, being particularly large in the first instar.

Ocelli are functionally absent and the prothorax is well-developed, to support the large fossorial forelegs. Later instars have conspicuous wing pads. The abdomen is fat and segmented. Nymphs are encased in a membrane on hatching; only the front legs are free, which they use to drag themselves out of the nest and then fall to the ground.

On hatching, they immediately bury themselves, in search of a root on which to start feeding.

Cicada nymphs feed on plant roots, digging deeper into the soil and using larger roots in successive instars. Feeding, in both nymphs and adults, is done by penetrating the xylem (not phloem as is the case with most sap-sucking insects).

This gives them a very watery, low sugar, and high amino acid diet.

The larvae build themselves cells to live in, often using the excess excreted moisture resulting from their feeding to cement the walls of their cells together. Generally, cicada nymphs go through 5 instars.

When they are ready to emerge as adults, the cicada nymphs return to near the soil surface and construct a waiting cell. Mostly these cells are immediately below the surface, but they may be as far as 30 to 60 cm down. These cells are often accompanied by a turret, constructed of soil particles that are glued together and erected above the soil surface.

In some places, these may be 6 inches (15cm) high and occur at a density of 25 per square foot (30 cm22). The exit hole can be at the base of the turret, giving it a blind tower for a roof. They remain in this cell until the weather conditions are right for them to emerge.

The nymph then climbs up some nearby vegetation and, at a certain variable height, emerges from his old skin into a beautiful flying and singing machine.

The time from emergence to being able to fly is about 2-3 hours in larger species but can be as quick as 30 minutes in smaller ones. There is a tendency for species to emerge in the evening but some species emerge in broad daylight.

Adults feed on the Xylem, the same as the nymphs, and this means that like other sap-feeding insects they have excess fluids; mostly water, as xylem fluid is low in sugars. To get rid of this while feeding, Diceroprocta apache a desert species found in Arizona USA, uses evaporation as a cooling method – allowing it to better survive the high temperatures experienced in this habitat.

Cicadas such as Magicicada septendecim exhibit a broad selection of host trees and it has been suggested, though not explained, that this is facilitated by the fact that the nymphs feed from the xylem rather than the phloem.

Cicadas have good eyesight and good hearing. Most adult cicadas are wary animals and use their wings to escape the attention of us humans.

A few species such as the New Zealand Melampsalta leptomera, a species which feeds on Maram Grass, use the more traditional homopteran response to a threat of dropping to the ground and feigning death.

Larger species will shriek if picked up and the resulting vibration can be quite surprising!

Most male Cicadas sing (i.e. produce sound), which is primarily what brings them to our attention. In most cases, as far as I know, the songs are sufficiently distinct to be of use in taxonomy.

Cicadas nearly always sing from a position of rest, normally on a piece of vegetation; but sometimes as in Okanagana palidula, from a hole in the ground. Singing while in flight is extremely rare, though it has been recorded from a few species.

Cicadas usually sing in a sunny spot and normally only on sunny days. In the past, the reluctance of cicadas to sing on damp days was said to be because their singing membranes were wet and thus not working. This is now known not to be the case.

Cicadas sing by using special muscles to buckle the ‘timbals’ (special ribbed chitinous membranes) located on the upper side of their 1st abdominal segment.

Cicadas make more than one sound, for instance, male Fidicina mannifera from Peru make 4 different sounds:

- a disturbance sound,

- a call,

- a low amplitude song, and

- their main song.

In this species, the males also engage in a stereotyped visual display called a ‘parallel walk’. This involves two males first calling back and forth, then lining up on a tree trunk; facing up the tree, and then walking side-by-side up the trunk, occasionally jostling one another for about 25 cm. This interesting action generally occurs between a territory-holding male and an intruder. In most cases, it is the intruder who flies away at the end of the ‘parallel walk’

Many generalist insectivores feed heavily on emerging cicada nymphs, which in periodical cicadas emerge in huge numbers in emergence years, every 13 or 17 years. This periodical life cycle makes it very difficult for predators or parasites to specialise in these species of cicadas – because for most they are only available once in several generations and not in between.

The only known specialist parasite of periodical cicadas is the fungus Massospora cicadina.

This flooding of the market for short periods is an unusual method of dealing with predators called ‘Predator Satiation’. This means that when the cicadas are around, there are just too many of them for their predators to deal with – and in this way, some survive to breed. Other insects such as mayflies, ants, and termites also indulge in this mass synchronised emergence strategy.

Ants are known to take a heavy toll on newly hatched cicada nymphs.

Ordinary cicadas also suffer from parasitism by fungi, particularly species of the genus Cordyceps, such as Cordyceps heteropoda – which specialise in using insects that spend part of their lives in the soil.

At least 11 species of wasps – nearly all in the Chalcidoidae and the families Eulophidae and Eurytomidae – are known to be egg parasites of cicadas. Some examples include Cerambycabius cicadae (a chalcid wasp laying one egg per egg) and Centrodara cicadae (a chalcid laying 1-3 eggs per egg); the larvae overwinter in the cicada’s egg and hatch next summer when a new lot of cicadas are laying eggs.

Cicada eggs also fall prey to various species of mites.

Solitary wasps such as Sphecius spectabilius in South America; Sphecius specious in North America; Sphecius freyi in Madagascar; and Exeirus lateritus in Australia, all provision their larval cells with cicadas.

Wasps such as Priocnemus bicolour (and some of the above) have been observed to grab a cicada by the leg and worry it until it flies off, whereupon the wasp drinks sap from the hole made by the cicada! Henri Fabre reports ants doing a similar thing.

Spiders inevitably take a toll on the adults, as do Robber Flies such as Neoartus Hercules in Australia and Neoitamus smithi in New Zealand

Huechys sanguinea is unusual in being warningly coloured, bright black and red; but reports differ over whether or not it is distasteful. It is commonly used by the Chinese for medicinal purposes.

Symbionts

Cicadas have fungi that live within them. These fungi are yeasts and occupy various places; sometimes these are special cells or organelles in the insect’s body called Mycetomes.

Relationships with Humans

Food

Mankind has long known of the singing cicada, but he has not only admired his singing. Cicadas were eaten in Ancient Greece, China, Malaya, Burma, Australia, North and South America, and the Congo – and probably everywhere else that they occur.

Medicine

Cicadas were used as a diuretic by peasants in Provênce. The exuviae are reported as being used as a cure for earache in China and Japan; while Huechys sanguinea an unusually coloured species (it is bright black and red) is commonly used by the Chinese for a variety of medicinal purposes.

Pests

Cicadas are not usually regarded as pests, though the noise they make can be quite deafening at times. However some species do achieve pest status if the conditions are right, a good example is Mogannia minuta on sugar cane in Japan.

Habitat Destruction

As a result of European settlement in N. America, most of the periodical cicada’s natural habitat has been destroyed. Surprisingly this has not resulted in a decrease in cicada numbers; they appear to have adapted to use roadside verges, orchards, and suburban street plantings instead.

Cicadas are mentioned in the Iliad by Homer about 10,000 BC. In the third book of the Iliad, Homer compares the discourse of “sage chiefs exempt from war” to the song of the Cicada.

Ancient Greeks and Chinese kept male Cicadas in cages, for the pleasure of hearing them sing. In fact, in ancient Greece, the cicada was sacred to Apollo the sun god. However, not everyone has been as charmed by them. In 1880 a guy called McCoy in Australia wrote of the Cicadas’ song:

“…it would tax the patience of a saint if such existed in Australia.”

About 1,000 BC, Hesiod wrote:

“When the Skolymus flowers, and the tuneful Tettix sitting on a tree in the weary Summer season pours forth from under his wings his shrill song.”

This record is interesting, in that the author has correctly located the source of the Cicadas’ song – even though he has not perhaps understood the mechanism of its production. Later writers were to be far less accurate in their descriptions, though not Aristotle who wrote on their morphology, song, and courtship.

Cicadas and Grasshoppers are often confused by ancient writers, or their later translators, particularly those who lived in northern Europe – and had no first-hand knowledge of the Cicada. The famous entomologist Henri Fabre explains that in Aesop’s Fable ‘The Grasshopper and the Ants’ (often quoted in Western Europe and its colonies as a moral lesson), i.e.,

“the hard-working ants and the lazy grasshopper who does naught but sing all through the summer”

The translation to grasshopper is incorrect. Fabre claims that Aesop when he wrote the original about 520 BC, was referring to a cicada. He then quite correctly points out that in reality, it is the ants that are lazy; displacing the Cicada from the hole she has drilled in the branch so that they can drink the nectar she has made available.

Yes, he admits that Cicada dies in winter but that is her allotted life span and not a fault; it is the projection of human character traits, either good or bad, onto groups of animals which is foolishness – not the habits of the cicadas.

Greek poets were for the most part lovers also of wine, and one ode to the cicada goes as follows;

“We call you happy, O Cicada, because after you have drunk a little dew in the treetops you sing like a queen.”

The interesting point here is the reference to cicadas feeding on dew. Many ancient observers had no real idea what cicadas fed on because they never observed them eating anything – their feeding being very discrete.

There is an ancient Italian myth which suggests that once there were no cicadas.

Then one day there was born on the Earth a beautiful, good, and very talented woman – whose singing was so wonderful it even enchanted the Gods. When she died, the world seemed so forlorn without the sweet sound of her singing, that the Gods allowed her to return to life every summer as the cicadas – so that her singing could lift the hearts of man and beast once again.

Cicadas had a powerful effect on other artists as well and they feature on numerous coins, both before and after the time of Christ.

As well as these, several beautiful gems have been found from around 300 BC, carved in the likeness of the cicada. Strangest perhaps are the ones which misplace the cicada’s role in the world; so that in one drawing we see a cicada pulling a plough, which is being driven by a locust; and in a mosaic from Pompeii, we see a cicada driving a carriage being pulled by a parrot.

The cicadas’ emergence from the Earth was a powerful symbol for ancient Romans, as it was for people in other parts of the world – particularly in the Far East. Members of the Roman nobility took to wearing a gold brooch featuring a cicada to hold back their hair. The people who followed this custom became known as the ‘Tettigophori’.

In Japan, the cicada was also a source of inspiration to poets and was known as Sémi or Semmi.

Fathomless deepens the heat;

The ceaseless shrilling of Sémi mounts,

Like a hissing fire, up to the motionless clouds.

Cicadas also feature in Japanese carving on such articles as medicine boxes (these were a bit like pill bottles, worn around the neck on a thong).

In Taoism, the cicada is the symbol of the hsien, or soul disengaging itself from the body at death.

In ancient China, a custom arose sometime after 1,000 BC of placing a jade carving of a cicada on a dead person’s mouth before burial – to aid the hsien or immortal soul as it seeks to leave the now useless body. In China, bronze artifacts depicting cicadas have been found dating back to 1,700 BC.

In 314 BC Kin Yuan wrote of someone’s death: “He divested of his body, as the cicada divests itself of the impure and abject.”

In Southern China, they are also known as ‘Hi-chee-sim’ (i.e., “Hi-chee insect”) because they appear when the hi-chee fruit is in season.

In India, the cicada is mentioned in ancient Hindu law as long ago as 200 BC. One example reads (and I do not sadly have an understanding of the relationship between salt and cicadas):

“Learn now, completely and in order, for what deeds committed here below (meaning on this earth), the soul must, to achieve expiation of its sins, enter into such or such a body. If it has stolen meat it must enter the body of a vulture; if it has stolen salt then the body of a cicada“

In the UK in the 15th century, Moufet wrote of cicadas as examples of moral goodness.

“It eats nothing belonging to the earth and drinks only dew, proving cleanliness, purity, and propriety; it will not accept wheat or rice, thus indicating its probity and honesty; how appealing to celestial conservatives! It appears always at a fixed time, showing it is endowed with fidelity, sincerity, and truthfulness.”

In some of the Maori folk laws of New Zealand, the cicada is known as the “Bird of Rehua”.

Rehua is the lord of kindness and plenty, which also perhaps reflects the cicadas summer emergence. Other Maori names for the cicada are onomatopoeic (a word which reproduces a sound i.e. ‘bang’) i.e. Kikihi or Kihikihi or Kikihitara (actually cicada and tettix are also onomatopoeic).

It is also of interest to note that the Maoris have a tale of ants and cicadas, which is very similar to Aesop’s fable. Maoris have also been known to see a similarity between the clicking of the Cicada and the English language; hence in Maori the word for Englishman is the same as the word for cicada!

In Sarawak-Malay (a Malaysian dialect) cicadas are “Kriang pakul anam”, or the “6 o’clock cicada” because of the regularity of their song. In other parts of the Malay peninsula, they are known as ‘riang riang’ and are supposed to sing because they are happy.

The Australian Aborigines, in at least one dialect, refer to cicadas as Galang Galang; and were, unlike most other ancient peoples, aware that only the males sing. A possible explanation for this is the greatly emphasized differences between males and females in some Australian species, i.e. the Bladder Cicada Cystosoma saundersi.

Lastly, the cicada mythology of the Zuni Indians of N. America contains a delightful tale, which goes something like this:

The Coyote was created with a nice even set of teeth, just like us. However, the ancestral coyote was travelling along one day when he heard a cicada singing; he thought the sound was beautiful and wanted the cicada to teach him the song. After some persuasion, the cicada agreed and taught it to him. Coyote then left, singing happily to himself.

Unfortunately, on the way home he had a bit of a mishap or accident and in the process of saving his skin, he forgot the song. Because he still wanted to know the song very much, he turned around and went back to the cicada and asked him to teach him the song again.

Cicada was enjoying the sun, but being a kind-hearted chap, he said OK. So he taught coyote the song again – and off went coyote again singing happily to himself once more. Unfortunately this time he was also distracted by something else on the way and forgot the song again.

He returned once more to the tree where the cicada was singing and begged to be taught the song again. So cicada taught him the song a third time – and watching coyote go off happily singing to no one in particular, he thought to himself.

“This Coyote chap has no brains, he will forget the song again and I will never have any peace.”

So, having thought about this, he decided to shed his skin. Then to make it look as if it was still occupied by his body, he put a small rock inside it and sewed it up. Then he flew to another tree to have a rest. Sure enough a few minutes later along comes coyote; seeing the cicada’s old skin and thinking it was cicada, he tells him of the awful accident that befell him on the way home – causing him to forget the song yet again – and begs Cicada to teach him the song again.

He gets no reply, but being a persistent sort of person, he carries on beseeching Cicada to teach him the song one more time – but through all his pleading and whining he gets no reply at all.

Eventually, he decides Cicada is just ignoring him, and this makes him angry. Now Coyote gets angry very quickly and when he is angry he is very nasty. So to punish Cicada for not answering him, he leaps up to the branch and bites what he thinks is Cicada as hard as he can. Coyote has very powerful jaws and biting the cicada’s empty skin with the stone inside wrecked his teeth so that now they are all uneven and jagged.

There is of course one very good reason why this couldn’t happen – and that is because Cicadas only sing after they have done their last skin shed.

Still, it is a lovely story and I hope you enjoyed it as much as I did when I first read it.

What Next?

Well, I hope this has been an interesting taste of the fascinating world of Family Cicadidae and the abundance of cicada mythology dating throughout history!

Perhaps now you’d like to check out the water striders.

Bibliography

- J.G. Myers (1929) Insect Singers: a Natural History of Cicadas. George Routledge and Sons. London.

- M.S. Moulds (1990) Australian Cicadas. New South Wales University Press, NSW. Australia

- Allen M. Young (1984) On the evolution of Cicada x Host-tree Associations in Central America. Acta Biotheoretica 33: pp 163-198

- Allen F. Sanbourn and Polly K.Phillips (1995) No Acoustic Benefit to Subterranean Calling in the Cicada Okanagana pallidula Davis (Homoptera: Tibicinidae). Great Basin Naturalist 55: 4 pp 374-376

- Reginald B. Cocroft and Michael Pogue (1996) Social Behaviour and Communication in the Neotropical Cicada Ficidina mannifera (Fabricius) (Homoptera Cicadidae). Journal of Kansas Entomological Society 69: 4 suppl. pp 85-99

- Robert l. Smith and William M. Langley (1978) Cicada Stress Sound: An Essay of its Effectiveness as a Predator Defense Mechanism. The Southwestern Naturalist 23: 2 pp 187-196

- Neil F. Hadely, Michael C. Quinlan and Michael L. Kennedy (1991) Evaporative Cooloing in the Desert Cicada: Thermal efficiency and Water/Metabolic Costs. J. exp. Biol. 159: pp 269-283

- Kathy S. Williams and Chris Simon (1995) The Ecology, Behaviour and Evolution of Periodical Cicadas. Annual Review of Entomology 40: pp 269-265

- YOSIAKI ITÔ and MASAAKI NAGAMINE (1981) Why a cicada, Mogannia minute Matsumura, became a pest of sugarcane: a hypothesis based on the theory of ‘escape’. Ecological Entomology 6: pp 273-283

Fungus image license: Creative Commons;

Coin / Jade image license (credit: Classical Numismatic Group / Didier Descouens): Attribution Share Alike.