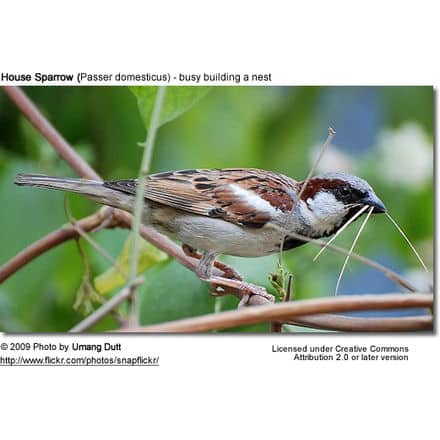

House Sparrows aka English Sparrows

The House Sparrows (Passer domesticus) is a member of the Old World (Europa, Asia, and Africa) sparrow family Passeridae.

Distribution / Habitat:

It occurs naturally in most of Europe and much of Asia. It has also followed humans all over the world and has been intentionally or accidentally introduced to most of the Americas, sub-Saharan Africa, and Australia as well as urban areas in other parts of the world.

In the United States, it is also known as the ‘English Sparrow’, to distinguish it from native species, as the large American population is descended from birds deliberately imported from Britain in the late 19th century.

They were introduced independently in a number of American cities in the years between 1850 and 1875 as a means of pest control.

Wherever people build, House Sparrows sooner or later come to share their abodes. Though described as tame and semi-domestic, neither is strictly true; humans provide food and home, not companionship. The House Sparrow remains wary.

Description:

The 14 to 16 centimetre long House Sparrow is abundant but not universally common; in many hilly districts, it is scarce. In cities, towns, and villages, even around isolated farms, it can be the most abundant bird.

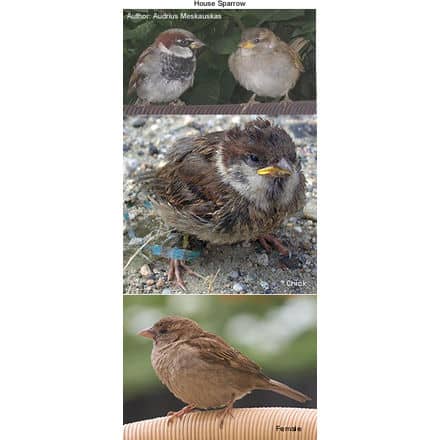

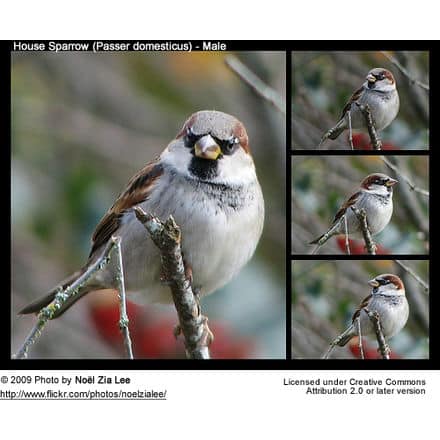

The male House Sparrow has a grey crown, cheeks, and underparts, black on the throat, upper breast, and between the bill and eyes. The bill in summer is blue-black, and the legs are brown. In winter the plumage is dulled by pale edgings, and the bill is yellowish brown.

The female has no black on her head or throat, nor a grey crown; her upperparts are streaked with brown. The juveniles are deeper brown, and the white is replaced by buff; the beak is dull yellow.

So familiar a bird should need little description, yet it is often confused with the smaller and slimmer Tree Sparrow, which, however, has a chestnut and not grey crown, two distinct wing bars, and a black patch on the cheeks.

The House Sparrow is gregarious at all seasons in its nesting colonies when feeding and in communal roosts.

Diet / Feeding:

Although the Sparrows’ young are fed on larvae of insects, often destructive species, this species eats seeds, including grain where it is available.

In spring, flowers, especially those with yellow blossoms, are often attacked and torn to bits; crocuses, primroses, and aconites seem to attract the House Sparrow most. The bird will also hunt butterflies.

Call / Song:

The short and incessant chirp needs no description, and its double call note Phillip which originated the now obsolete popular name of “Phillip Sparrow”, is as familiar.

While the young are in their nests, the older birds utter a long churr. At least three broods are reared in the season.

Nesting

The nesting site is varied; under eaves, in holes in masonry or rocks, in ivy or creepers on houses or banks, on the sea cliffs, or in bushes in bays and inlets. When built in holes or ivy the nest is an untidy litter of straw and rubbish, abundantly filled with feathers. Large, well-constructed domed nests are often built when the bird nests in trees or shrubs, especially in rural areas.

The House Sparrow is quite aggressive in usurping the nesting sites of other birds, often forcibly evicting the previous occupants, and sometimes even building a new nest directly on top of another active nest with live nestlings. House Martins, Bluebirds, and Sand Martins are especially susceptible to this behavior. However, though this tendency has occasionally been observed in its native habitats (particularly concerning House Martins), it appears to be far more common in habitats in which it has been introduced, such as the USA.

Five to six eggs, profusely dusted, speckled, or blotched with black, brown, or ash-grey on a blue-tinted or creamy white ground, are usual types of very variable eggs. They are variable in size and shape as well as markings. Eggs are incubated by the female. The House Sparrow has the shortest incubation period of all the birds: 10-12 days and a female can lay 25 eggs a summer in New England.

House Sparrows in Europe

In large parts of Europe, populations of House Sparrows are decreasing. In the Netherlands, the House Sparrow is even considered an endangered species. It is however still the second most common breeding bird in the Netherlands, after the Blackbird. The population of House Sparrows has halved in the period around 1980 till now. Currently, the number of breeding pairs is estimated at half a million to one million. Similar precipitous drops in population have also been recorded in the United Kingdom.

Various causes for its dramatic decrease in population have been proposed:

- More and more houses were built without roof tiles, or the construction of the roofs was so well done, that the sparrows did not have space left for building their nests;

- Decades ago, when the horse and carriage were replaced by cars, less grain was spilled in the streets;

- Agricultural changes: often other crops than corn and grain were cultivated, and more insecticides were used, which meant a decrease in the number of insects that can be eaten by sparrows;

- More efficient building in cities which resulted in less rough areas within cities where the birds could find food;

- It became less usual in households to shake the tablecloths outside after meals;

- Changes in gardening fashions left fewer suitable nesting spots for sparrows.

House Sparrows in North America

While declining somewhat in their adopted homeland, house sparrows are still possibly the most abundant bird in the United States, with a population estimated as high as 400 million.

In the United States, the House Sparrow is one of three birds not protected by law (the others are the European Starling and Rock Pigeon, also introduced species). House Sparrows sometimes kill adult Bluebirds and other native cavity nesters and their young and smash their eggs. The House Sparrow is partially responsible for the near extinction of Bluebirds in the United States.

House Sparrows often take over unmonitored nest boxes and Purple Martin houses in the United States. This invasion has led many nestbox monitors in the United States to trap or shoot the adults and take their eggs to allow native species to reproduce. European Starlings are aggressive enough to take nests from House Sparrows in the United States if the entrance hole is big enough for them to fit through.