Acorn Woodpeckers (Melanerpes formicivorus)

The Acorn Woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus) – also known as Narrow-fronted Woodpecker – is quite a busy, social bird, living year-round in communal family groups of as many as 15 birds.

These groups are known as “bushels” of woodpeckers and are comprised of siblings, their cousins, and their parents.

As these birds soar in their undulating flight pattern, the bird-watcher can catch a glimpse of the white circles on their wings. Their unusual, laugh-like call identifies them in the field.

This mid-sized woodpecker is a permanent resident throughout its range; however, they may relocate to another area if acorns are not readily obtainable.

Other birds hoard, but none does it on such a grand scale as the Acorn Woodpecker. They stash their acorns in what is termed a “granary tree;” these are storage trees into which the woodpeckers pack acorns for future retrieval.

These trees may be storehouses for a bushel of woodpeckers for many generations. The granary is usually a tree, but it can also be a fence, telephone pole, or siding on a building. As they stock up for winter, they will fill the tree with a bounty of acorns.

In habitats with a temperate climate, the birds within the bushel do not typically forage at the same time, but those dwelling in the tropics often forage and travel together. Some groups will migrate in order to take advantage of seasonal increases in insect populations.

Unafraid of humans, they have been known to follow picnickers, cleaning up the scraps they’ve left behind.

They will dwell in both urban and suburban neighborhoods as long as there are plenty of acorn-bearing oak trees available. This species chooses the highest elevations possible in their range.

The homeowner may find his wood siding riddled with holes as a result of the Acorn Woodpecker’s drilling, and it isn’t an easy task to discourage the woodpeckers from this behavior.

Some have found that hanging strips of shiny ribbon from the eaves or tying balloons in front of the siding will frighten the birds away, but the only permanent solution is to replace the siding with an impenetrable material.

Distribution / Habitat

This is a sedentary species, living year-round on the West Coast and nearby states. Their territory ranges from southern Oregon, south through California, Arizona, New Mexico, and western Texas. They can also be found in Colorado, Utah, and the tropics.

Besides dwelling in the American Southwest, this bird inhabits parts of western Mexico, the Central American highlands, and farther south into the northern Andes of Colombia.

Acorn Woodpeckers occupy western oak woodlands, preferably the open oak and pine-oak forests. They may also be seen in savannahs, chaparral, mixed oak-conifer forests on slopes, mountain forests, and riparian woodlands in the southwest and west coast.

They will frequent towns and suburbs as long as oaks trees bearing plenty of acorns and suitable places to store them are accessible. Douglas firs, redwood and tropical hardwood forests, urban parks, and rural areas are among choice locations for the Acorn Woodpecker.

Subspecies and Ranges:

- North American Acorn Woodpecker (nominate) (Melanerpes formicivorus formicivorus – Swainson, 1827)

- Range: Southern United States, from Arizona east through New Mexico and western Texas south through the southeastern parts of Mexico, west of the southernmost State of Mexico, Chiapas.

- Columbean Acorn Woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus flavigula – Malherbe, 1849)

- Range: This Colombian species is found in western and central Andes mountain range and on the western slope of the eastern Andes.

- California Woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus bairdi – Ridgway, 1881)

- Range: In the USA, from northwestern Oregon south to northern Baja California in Mexico.

- Acorn Woodpecker (albeolus) (Melanerpes formicivorus albeolus – Todd, 1910)

- Range: Southeastern Mexico – from eastern Chiapas and probably also Tabasco and Campeche), south to northeastern Guatemala and Belize.

- Acorn Woodpecker (lineatus) (Melanerpes formicivorus lineatus – Dickey and van Rossem, 1927)

- Range: Southeastern Mexico, from Chiapas east to Guatemala and northern Nicaragua.

- Acorn Woodpecker (striatipectus) (Melanerpes formicivorus striatipectus – Ridgway, 1874)

- Range: Central America, from Nicaragua to western Panama.

- Acorn Woodpecker (San Lucan) (Melanerpes formicivorus angustifrons – Baird,SF, 1870)

- Range: Extreme Southern Baja California.

- [Melanerpes formicivorus phasma (Oberholser, 1974)] – mostly considered invalid

- [Mearns’s Woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus aculeata – Mearns, 1890)] – mostly considered invalid

- [San Pedro Woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus martirensis – Grinnell and Swarth, 1926)] – mostly considered invalid

- [Ant-eating Woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus uropygialis – Baird,SF, 1854)] – mostly considered invalid

Description

Size

The wing span of the Acorn Woodpecker ranges between 5 ½- 6 in (13-15 cm), and the bird measures 8 ¼ in (21 cm) long and weighs about 3 oz (85 g).

Plumage Details / Adults

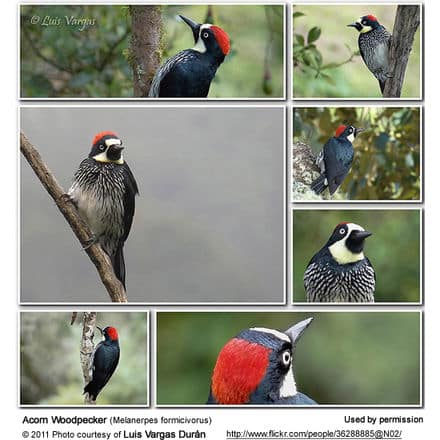

The Acorn Woodpecker has been described as “comical-looking,” and having a “clown face.” It is a medium-sized woodpecker with a brownish-black head, back, wings and tail.

The upperparts are glossy black, while the underparts are white with streaks of black. The forehead, neck, throat, belly, and rump display white patches.

The eyes are encircled by distinctive white markings, and the face, neck, and throat exhibit black, yellow, and white markings.

A few green feathers adorn the rump area, and white patches can be found on their wings and rump. In flight, they reveal three patches of white—one on each wing and one on the rump.

The adult male has a red cap starting at the white forehead, whereas females have a black area between the forehead and the red crown.

In Colombian populations, the male has a solid red crown while the female has a black band separating the red crown from the white forehead.

Other Physical Details

Their rigid, pointed, wedge-shaped tails serve as supports for the birds as they climb and cling to branches and tree trunks. Their zygodactyl toes assist them in climbing and clinging. An extremely hard, heavily keratinized sheath covers the beak, and the point is sharp, straight, and chisel-shaped.

Gender ID

Females have bills that are slightly shorter than the males’ bills, and their crowns are a lighter red than the males’.

Juvenile Description

The juvenile’s appearance is similar to the female, but he has darker eyes and is more brown than black in color.

Diet / Feeding

Acorn Woodpeckers, as their name implies, depend heavily on acorns for food. In some parts of their range (e.g., California), they seek out the perfect tree to be their granary.

This is usually an oak tree, but sometimes they will pack their acorns in the soft wood of the palm tree. The woodpeckers then collect acorns and position them either in existing holes or freshly drilled holes that are the perfect size for each acorn.

As the acorns dry out, the woodpecker must transfer them to smaller holes. This is a tremendous energy investment, consuming a significant amount of the birds’ time.

Because these acorns are visible, even more energy must be expended defending their cache against robbers, such as squirrels, Steller’s Jays and Western Scrub Jays.

One of the purposes of communal living is to stockpile as many acorns as possible. The other is for the protection and defense of the granary against other birds and animals that attempt to steal the acorns.

The California populations are so dependent on this valuable resource that they may even resort to nesting in the fall to take full advantage of the fall acorn crop. (Late nesting is almost unheard of in birds.)

Once in a while, the acorns are jammed in so tightly that even squirrels are unable to pry them out. Some of these granary trees have up to 50,000 holes drilled in them by extended woodpecker families!

The woodpeckers will re-use their granary trees from year to year, refilling the existing holes. A cache this huge requires a sizeable family group to defend their granary tree. If they run out of acorns, they might migrate south.

In some parts of its range, the Acorn Woodpecker does not construct a “granary tree,” but instead stores acorns in natural holes and cracks in bark. If the acorns are eaten, the woodpecker will move to another area, even if it means migrating from Arizona to Mexico to spend the winter.

The Acorn Woodpecker does not limit its granary stores to trees; it will use any man-made structure to accumulate acorns, drilling holes into fence posts, utility poles, buildings, bridges, siding on houses, and even automobile radiators!

Occasionally, a woodpecker will hoard the acorns in places where it cannot get them out. A group of woodpeckers once packed 220 kg (490 lb) of acorns into a wooden water tank in Arizona and was unable to reclaim them.

Their stash of nuts appears to be an emergency provision, to be accessed on cold, winter days. For the most part, they will fly to the ground only momentarily to retrieve acorns, collecting just one acorn at a time; but some have been observed breaking off a twig which might hold as many as three acorns.

Acorn Woodpeckers consume other foods in addition to acorns. On warmer days, they dart from tree to tree in order to feed on insects, fruit, and seeds.

Foraging for insects often takes place at the tops of trees, near the canopy, and these too will be stored in cracks or crevices. In the summer, they will catch insects on the fly and forage for ants, nectar, lizards, and bird eggs.

Other foods include oak catkins, grass seeds, lizards, flying ants, fruit, and flower nectar. These birds can often be seen at seed and suet feeders near oak woodlands within their range. In order to obtain liquids, they will drill out deeper holes in the wood so that they can drink the sap.

Sapsucking is a collective activity; the entire group will congregate at a source and feed. This group of trees will be used for several years.

Breeding / Nesting

Acorn Woodpeckers breed between May and July. They choose forested habitats with great expanses of oak trees for nest-building.

Favored nesting locations include the hills of coastal areas and foothills of California and the southwestern United States south to Colombia. This species chooses low elevations in the northern ranges, but rarely below 1000 m in Central America, and it will build its nests up to the timberline.

The nesting pair and their extended family choose a dead tree or part of a tree in which to drill out their cavity.

Observations of this extended group have noted that the number of birds engaging in this activity can range from only a single pair to a group of seven males and three females; in addition, as many as ten non-breeding helpers may participate.

An Acorn Woodpecker group may consist of 1–7 male breeders that compete to mate with 1–3 females so not every bird in the group will mate each year. Courtship rituals are similar to those of other woodpeckers; however, these only take place between monogamous pairs.

They include bowing, wing spreading and aerial displays. If there are multiple males and females breeding in a communal nest, there are no courtship displays.

All breeding males can mate with any and all of the female breeders of the group; however, the female Acorn Woodpecker does the choosing. She will mate with as many as four males; this means the young are a result of “extra-pair paternity.”

All members of the group are close relatives except the co-breeder males. They are not related to the nest-sharing females. The bushel will choose a large tree in which to excavate the nest, and then they will line the nest with wood chips; this same tree usually doubles as their granary tree. Tree cavities are built in both dead and living trees, and the pear-shaped nest hole will continue to be used by the pair in future breeding seasons.

In groups with more than one breeding female, the females lay their eggs in a single nest cavity. Each female lays 4-6 white, elliptical eggs; she will then attempt to destroy the other hens’ eggs during the egg-laying period. They will even remove each other’s eggs from the nest!

Once all of the eggs have been laid (generally at 24-hour intervals), the attacks on the eggs cease; nonetheless, as many as one-third of the eggs will be destroyed during this time.

There is an 11-14-day incubation period during which the parents and the other members of the community share incubation duties. After hatching, the chicks are attended to by both parents and the non-breeding helpers (young from previous years).

The fledglings will make their initial flight approximately 30–32 days after hatching and return to the nest to be fed for several weeks. Young woodpeckers stay with their community for several years to assist with the care of the nestlings.

Calls / Vocalizations – Sound and Video Recordings

They have several vocalizations. One of their calls is a loud “rach-et, rach-et, rach-et” sound. Another is constant chattering which imitates laughter.

Their louder “waka-wak” calls are to set off an alarm, mostly given when the granary is under attack. A group member is always on alert to guard the hoard from thieves, while others race through the trees screaming the parrot-like “waka-waka” calls.

This call is also observed when the birds land near each other, and it probably serves as a greeting. If it is given more quietly, with the wings held slightly open, it is thought to be a subtle form of communication.

A photographer’s delight, the Acorn Woodpecker puts on quite dramatic displays. His various calls appear to play an important part in the group’s dynamics.

If several group members converge on the same spot, they will produce a noisy spectacle; this attracts the attention of the rest of the bushel, and they will assemble. These displays frequently occur during territorial encounters and boundary disputes.

https://www.xeno-canto.org/embed.php?XC=105667

https://www.youtube.com/embed/aWe1tktK918

Alternate (Global) Names

Chinese: ????? … Czech: Datel sberac / sb?ra? … Danish: Agernspætte …Dutch: Eikelspecht … Estonian: Tõrurähn … Finnish: Terhotikka … French: Pic des chênes, Pic glandivore … German: Eichelspecht … Italian: Picchio delle ghiande … Japanese: Dongurikitsutsuki … Norwegian: Eikespett … Polish: Dzieciur zoledziowy / ?o??dziowy … Russian: ????????? ?????, ?????????? ?????????? … Slovak: tesárik dubový … Spanish: Carpintero Arlequin, Carpintero Arlequín / Bellotero / Careto, Carpintero de Robledales, Cheje bellotero, Garacaca … Swedish: Samlarspett

Conservation / Status

Just as are most species today, the Acorn Woodpeckers are threatened by habitat loss and degradation. The birds must compete with non-native species for choice tree locations, particularly in the more populated areas.

Functioning ecosystems must be preserved in order to provide the birds with all of the resources they require. Mature forests with oaks that produce large mast crops and nesting and roosting sites are becoming more difficult for the birds to find.

Homeowners are encouraged to aid in the preservation of the Acorn Woodpecker populations by providing and preserving mature oak and pine-oak stands of trees and by allowing dead trees and limbs to remain.

Member of the Picidae Family: Woodpeckers … Sapsuckers … Flickers

Beauty Of Birds strives to maintain accurate and up-to-date information; however, mistakes do happen. If you would like to correct or update any of the information, please contact us. THANK YOU!!!