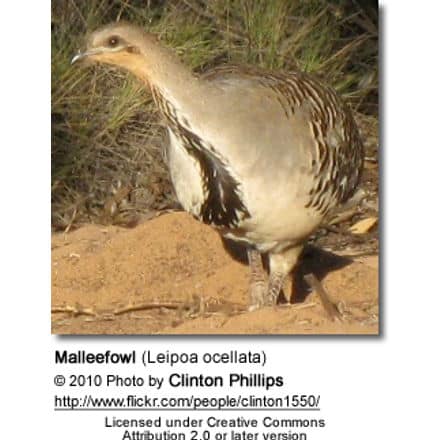

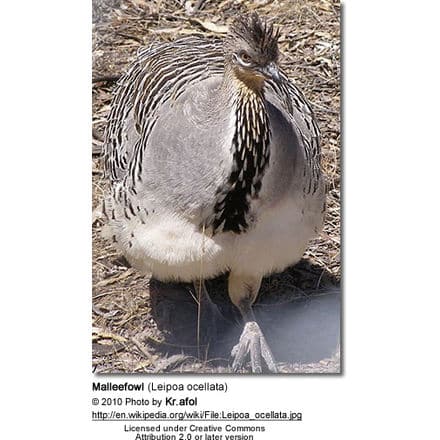

Malleefowl

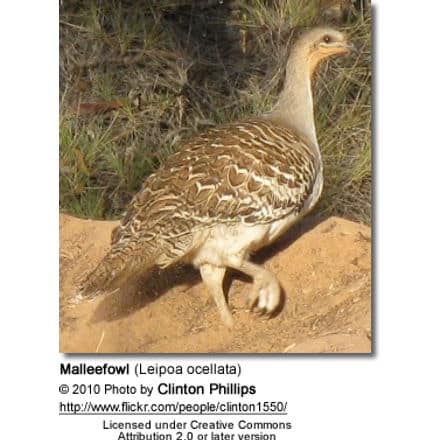

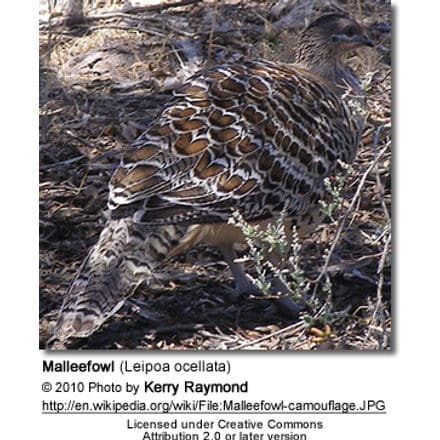

The Malleefowl (Leipoa ocellata) is a stocky ground-dwelling Australian bird about the size of a domestic chicken (to which it is distantly related).

It occupies semi-arid mallee scrub on the fringes of the relatively fertile areas of southern Australia, where it is now reduced to three separate populations: the Murray-Murrumbidgee basin, west of Spencer Gulf along the fringes of the Simpson Desert, and the semi-arid fringe of Western Australia’s fertile south-west corner.

Behavior

Malleefowl are shy, wary, solitary birds that usually fly only to escape danger or reach a tree to roost in.

Although very active, they are seldom seen as they freeze if disturbed, relying on their intricately patterned plumage to render them invisible, or else fade silently and rapidly into the undergrowth (flying away only if surprised or chased).

They have many tactics to run away from predators.

Reproduction

Pairs occupy a territory but usually roost and feed apart: their social behavior is sufficient to allow regular mating during the season and little else.

In winter, the male selects an area of ground, usually a small open space between the stunted trees of the mallee, and scrapes a depression about three metres across and just under a metre deep in the sandy soil by raking backward with his feet. In late winter and early spring, he begins to collect organic material to fill it with, scraping sticks, leaves, and bark into wind rows for up to 50 metres around the hole, and building it into a nest mound, which usually rises to about 0.6m above ground level. The amount of litter in the mound varies, it may be almost entirely organic material, mostly sand, or anywhere in between.

After the rain, he turns and mixes the material to encourage decay and, if conditions allow, digs an egg chamber in August (the last month of the southern winter). The female sometimes assists with the excavation of the egg chamber, and the timing varies with temperature and rainfall. The female usually lays between September and February, provided there has been enough rain to start the organic decay of the litter. The male continues to maintain the nest mound, gradually adding more soil to the mix as the summer approaches (presumably to regulate the temperature).

Males usually build their first mound (or take over an existing one) in their fourth year, but tend not to achieve as impressive a structure as older birds. They are thought to mate for life, and although the male stays nearby to defend the nest for nine months of the year, they can wander at other times, not always returning to the same territory afterward.

The female lays a clutch of anywhere from two or three to over 30 large, thin-shelled eggs, mostly about 15; usually about a week apart. Each egg weighs about 10% of the female’s body weight, and over a season it is common for her to lay 250% of her own weight. Clutch size varies greatly between birds and with rainfall. Incubation time depends on temperature and can be anywhere between about 50 and almost 100 days.

Hatchlings use their strong feet to break out of the egg, then lie on their backs and scratch their way to the surface, struggling hard for five or ten minutes to gain 3 to 15 cm at a time, and then resting for an hour or so before starting again. Reaching the surface takes between 2 and 15 hours. Chicks pop out of the nesting material with little or no warning with, eyes and beak tightly closed, then immediately take a deep breath and open their eyes, before freezing motionless for as long as 20 minutes.

The chick then quickly emerges from out of the hole and rolls or staggers to the base of the mound, disappearing into the scrub within moments. Within an hour it will be able to run reasonably well; it can flutter for a short distance and run very fast within two hours, and despite not having yet grown tail feathers, it can fly strongly within a day.

Chicks have no contact with adults or other chicks: they tend to hatch one at a time and birds of any age ignore one another except for mating or territorial disputes.

Conservation status

Across its range, the Malleefowl is considered to be threatened. Predation from the introduced red fox is a factor, but the critical issues are changed fire regimes and the ongoing destruction and fragmentation of habitat.

Like the Southern Hairy-nose Wombat, it is particularly vulnerable to the increasing frequency and severity of drought that has resulted from climate change.

Before the arrival of Europeans, the malleefowl was found over huge swathes of Australia.

International

The Malleefowl is classified as endangered on the IUCN Red List.

Australia

Malleefowl are listed as vulnerable in the Australian Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Its conservation status has varied over time and also varies from state to state within Australia. For example:

- The Malleefowl is listed as threatened by the Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act (1988). Under this Act, an Action Statement for the recovery and future management of this species has been prepared.

- On the 2007 advisory list of threatened vertebrate fauna in Victoria, the Malleefowl is listed as endangered.

- The Malleefowl is listed as vulnerable on schedule 8 of the South Australian National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972.

- Malleefowl are listed as endangered in the New South Wales Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995.

Yongergnow Australian Malleefowl Centre

The Yongergnow Australian Malleefowl Centre is located at Ongerup, Western Australia, on the road between Albany and Esperance. The centre opened in February 2007 and is intended to provide a focal point for education about the malleefowl and the conservation of the species.

There is a permanent exhibition and a large aviary containing a pair of malleefowl. The centre collects reported sightings of the malleefowl.

Megapode Information … Megapode Photo Gallery