Phylum Acanthocephala (Spiny Headed Worms)

Acanthocephala Etymology: From the Greek Acantha a prickle, and Kephale a head.

Acanthocephala Species Count:- There are currently (April 18 2021) 1,330 species of Ancanthocephala recorded in the online database Catalogue of Life

Characteristics of Acanthocephala:

- Bilaterally symmetrical and vermiform.

- Body has more than two cell layers, tissues and organs.

- Body cavity is a pseudocoelom.

- Body possesses no digestive system.

- Body covered by a syncitial epidermis with a few giant nuclei.

- Has a nervous system with a ganglion and paired nerves.

- Has no true circulatory or respiratory organs.

- Reproduction sexual and gonochoristic, with vivparous embryos.

- Adults parasitic on vertebrates.

- Larvae live in insects and crustaceans.

Introduction to the Acanthocephala

Acanthocephala is a medium sized phylum (1,330 species) of usually small and always parasitic and unsegmented worms. Over 1,000 have been found in the gut of a single seal. Acanthocephalans are aquatic worms and live in both marine and fresh water habitats. They are all parasites living and feeding in their hosts alimentary canal. Their primary host is usually a fish and the intermediate host an arthropod, usually a crustacean or an insect.

Although fish are the main primary host for the majority of acanthocephalans they may also parasitize amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. They are occasionally found in humans where infection is accidental. Acanthocephalans do little damage to the hosts they parasitize and are not considered dangerous or economically important.

Most are less than 25mm or 1 inch long, though some species may attain a length of nearly a metre.

They get the name of Spiny Headed Worms (or sometimes Thorny Headed Worms) from their proboscis, which possesses several rings of backwardly curving spines that they use to attach themselves to the walls of their host’s digestive system. This proboscis can be retracted within the body wall by muscular contraction, but it can also be everted, extended again, by hydraulic pressure.

Anatomy of Acanthocephalans

As is the case with many parasites, acanthocephalans have lost many of their organs and tissues – retaining only those they need to grow and to reproduce. Acanthocephalans are pseudocoelomate and possess a unique epidermis which contains a lacunar system (an interconnected fluid-filled network of cavities). The epidermis also has some hollow tubular muscles.

Thus they have no circulatory, digestive or respiratory organs. Everything just passes in and out through their cuticle. They have a simple nervous system, comprising a single ventral ganglion in the proboscis and a few nerves. They do have reproductive organs though and as with many parasites (such as flukes) a complicated life cycle, involving more than one host.

The acanthocephalan body is comprised of a proboscis and an elongated cylindrical trunk. The proboscis, which carries the backward-pointing hooks that give the animals their common name, can be withdrawn into the trunk. This trunk may also bear hooks or spines. In colour Acanthocephalans are usually a dirty white, though a few species are yellow, orange, or red.

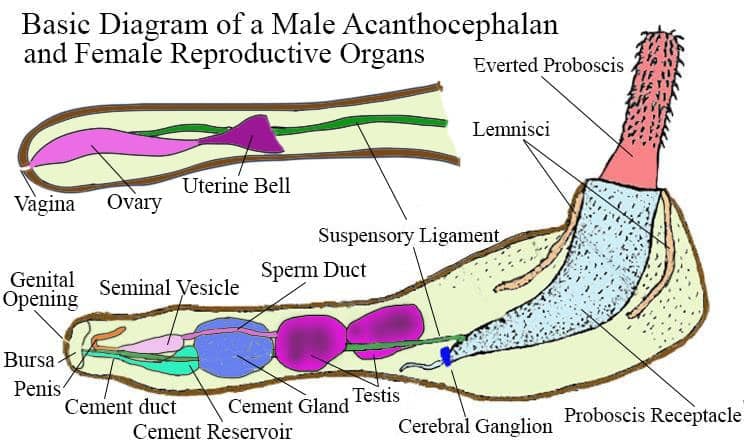

The internal anatomy is simple; there is no gut, and the bulk of the trunk is occupied by a proboscis receptacle and the muscles used to retract it. Passing backward from the base of this receptacle are structures known as ligament sacs. One of these sacs in the male encloses two testes and a number of cement glands. Two fluid-filled structures called ‘lemnisci are found at the sides of the proboscis. These lemnisci provide the hydraulic system that allows the proboscis to be everted, thus their shape changes depending on whether or not the proboscis is everted.

Acanthocephalans possess a single large nerve ganglion which is situated at the base of the proboscis receptacle. From this extend paired lateral nerve cords with nerves going to the body wall, the genital area and the proboscis. Males posses and extra ganglion in the genital region and appear to have sense organs in this area as well, especially on the tip of the penis, Brusca & Brusca 2003.

Acanthocephalan Reproduction

Acanthocephalans are dioecious, meaning the come in male and female and (unusually for invertebrates) the males have a penis and the females have a vagina.

The first step in the reproductive cycle is copulation, which occurs in the vertebrate host’s guts. Males also have several cement glands, which they use to seal the female’s vagina after copulation. The eggs are fertilised by the sperm within the female’s body cavity and embryonic development occurs their as well. Cleavage is holobalstic and unequal, often described as spiral, this produces a steroblastula.

Early embryonic development continues within the female’s body cavity. Once they are developed beyond a certain level the embryos are collected into the uterus through a unique organ called the uterine bell. This uterine bell actively chooses to only accept embryos that have reached the required level of development, quite how it does this is not know, but it involves the uterine muscularly manipulating the embryos. The ovary is connected to the suspensory ligament and serves the purpose of guiding the developed embryos to the genital pore and out into the hosts digestive tract.

After a certain degree of development, the larvae become encapsulated and these ‘shelled’ or ‘encased’ larvae are called Acanthors. They are released by the female into the host’s guts, where they pass out with the faeces. An adult female may release hundreds of thousands of these acanthor larva into the host gut on a daily basis, Pechenic 2015. These acanthor larva possess a hooked rostellum that they will use to attach themselves to the new host’s tissue. The acanthors then remain dormant until eaten by the secondary – or intermediary – host, which is often a crustacean.

Once inside the secondary host’s guts, the shell dissolves and the acanthor hatches into a second stage larvae called an Acanthella.

After reaching their full size, they encyst themselves in their secondary host’s tissues where they remain dormant until the secondary host is eaten by the primary host. This encysted stage is called a Cystacanth.

Many acanthocephalan primary hosts are carnivores, or at least omnivores, as this helps ensure the fulfilling of the life cycle by increasing the chances of the secondary host being eaten by the primary host. Some species manage to change the habits of their secondary host, to make it more likely that it is eaten – by making it stay out in the open for instance.

Taxonomy

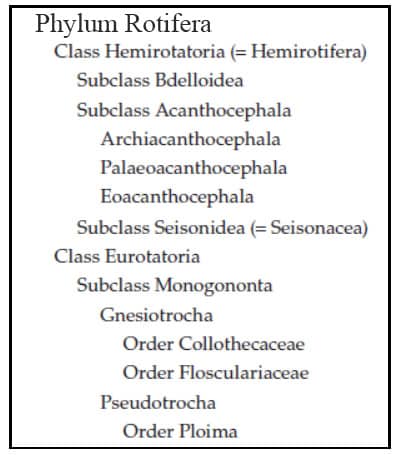

As with all the animal phyla, the taxonomy of the phylum Acanthocephala is under discussion, with new data, and new interpretations of genetic analyses resulting in people developing different ideas on the true relationships between different groups of organisms. What I have laid out below is the traditional view, supported by most text books. However in 2020 a quite different view was upheld in the book “The Invertebrate Tree of Life” by Giribet and Edgecomb (Princeton University Press 2020). In this scheme the Phylum Rotifera would include the Phylum Acanthocephala (which would cease to by an independent phylum) see box below.

Currently (April 2021) the phylum Acanthocephala is divided into four classes, ten orders, 26 families and 122 genera. For more detailed taxonomy than is given below see Classification of the Acanthocephala by Omar M. Amin 2013; 32 species have been added since this paper was published.

Phylum Acanthocephala • 1,330 described species

- Class Archiacanthocephala • 187 spp.

- Order Apororhynchida • 7 living spp.

- Family Apororhynchidae • 7 living spp.

- Order Gigantorhynchida • 64 living spp.

- Family Giganthorhynchidae • 64 living spp.

- Order Moniliformida • 20 living spp.

- Family Moniliformidae • 20 living spp.

- Order Oligacanthorhynchida • 96 living spp.

- Family Oligacanthorhynchidae • 96 living spp.

- Order Apororhynchida • 7 living spp.

- Class Eoacanthocephala • 255 living spp.

- Order Gyracanthocephala • 98 living spp.

- Family Quadrigyridae • 98 living spp.

- Order Neoechinorhynchida • 157 living spp.

- Family Dendronucleatidae • 3 living spp.

- Family Neoechinorhynchidae • 152 living spp.

- Family Tenuisentidae • 2 living spp.

- Order Gyracanthocephala • 98 living spp.

- Class Palaeacanthocephala • 884 living spp.

- Order Echinorhynchida • 524 living spp.

- Family Arhythmacanthidae • 49 living spp.

- Family Cavisomidae • 27 living spp.

- Family Diplosentidae • 8 living spp.

- Family Echinorhynchidae • 171 living spp.

- Family Fessisentidae • 6 living spp.

- Family Gymnorhadinorhynchidae • 1 living spp.

- Family Heteracanthocephalidae • 9 living spp.

- Family Illiosentidae • 50 living spp.

- Family Isthmosacanthidae • 1 living spp.

- Family Pomphorhynchidae • 51 living spp.

- Family Rhadinorhynchidae • 147 living spp.

- Family Sauracanthorhynchidae • 1 living spp.

- Family Transvenidae • 3 living spp.

- Order Heteramorphida • 1 living spp.

- Family Pyrirhynchidae • 1 living spp.

- Order Polymorphida • 359 living spp.

- Family Centrorhynchidae • 121 living spp.

- Family Plagiorhynchidae • 90 living spp.

- Family Polymorphidae • 148 living spp.

- Order Echinorhynchida • 524 living spp.

- Class Polyacanthocephala • 4 living spp.

- Order Polyacanthorhynchida • 4 living spp.

- Family Polyacanthorhynchidae • 4 living spp.

- Order Polyacanthorhynchida • 4 living spp.

General References

- Jan A. Pechenik – Biology of the Invertebrates McGraw-Hill Education (2015)

- R. C. Brusca and G. J. Brusca – Invertebrates 2nd Edition Sinauer Associates (OUP) (2003)