Class Scaphopoda (Tusk Shells)

Etymology = From the Ancient Greek skáphē = boat, + poús/poda = foot :- Boat footed

Species Count = Catalogue of Life: 2019 Annual Checklist = 576; Molluscabase = 611

Fossil Species = Molluscabase = 35

Condition of Typical Molluscan Characteristics

- Radula (a rasping “tongue” with chitinous teeth) = Present – Internal, cannot reach outside the body.

- Odontophore = (cartilage that supports the radula) = Present.

- Large Complex Metanephridia = Small and simple.

- Broad Muscular Foot = Reduced – only at the front of the animal.

- Large Digestive Ceca = Absent.

- Visceral Mass = Present.

- Shell = One.

- Habitat = Marine.

- Reproduction (Genders) = Dioecious (male and female in separate bodies)

Introduction to the Scaphopoda (Tusk Shells)

The Scaphopoda are small but interesting class of molluscs. Their common name is Tusk Shells because the curved, hollow and cylindrical shells resemble small tusks. One of the most distinctive aspect of the Scaphopodan shell is that it is a cylinder and open at both ends. The larger aperture is where the foot and ‘head’ area are located. Scaphopods orient head down, usually at a 30 to 40 degree angle. So, in contrast to many depictions, the animal is buried with the larger end of its shell deepest in the sediment.

The Scaphopoda are broadly distributed around the globe, occurring in tropical, temperate and arctic/antarctic waters. They are also widely distributed in terms of water depth. A few species are known from the lower intertidal zone (low tide area) such as Polyschides tetraschistus, but generally they like to be well under the water all the time. They prefer depths of 50 meters or more, the deepest known living species is Siphonodentalium galatheae which occurs at a depth of 7000 metres.

Taxonomy and Evolution of Tusk Shells

The class Scaphopoda is divided into two orders Dentaliidae and Gadilida, these break down into 12 extant families and 46 genera. However new species are still being regularly discovered. The Dentaliidae (287 species) and Gadilida (279 species) are distinguished by their shell structures.

The Dentaliidae have shells that are strong and longitudinally ribbed, at least near the apex, and which reach their widest circumference at the anterior end. In contrast the shells of the Gadilida are generally smaller and smooth surfaced and widest shortly before the anterior end. Scaphopods are relatively small molluscs ranging in size from around 5 mm in shell length to 19 cm in shell length.

The tusk shells appear to be the most recently evolved of the molluscan classes. The oldest fossil fully accepted records of scaphopods have been found in the late Devonian era 360 MYA. However some scientists consider Rhytiodentalium kentuckyensis, from the mid-Ordovician (460 MYA) to be the first fossil record of a scaphopoda.

The scaphopoda are generally considered to be most closely related to the cephalopoda. However the exact relationship of the scaphopoda to other molluscan classes is still uncertain and hopefully we will know more in the future.

Basic Biology of the Scaphopda

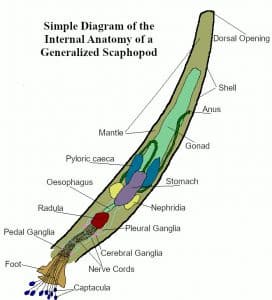

The scaphopoda are bilaterally symmetrical, and live with their body completely surrounded by the shell, which encloses the mantle cavity. The body is connected to the dorsal part of the shell by the mantle and is surrounded laterally and ventrally by the mantle cavity.

The two different orders of tusk shells display different behaviour when feeling threatened. The generally larger dentaliidae freeze and remain completely immobile when they sense danger. However Gadilidans prefer to avoid danger by moving rapidly through the substrate. This is undoubtedly made easier by the smooth surface of their shells.

Scaphopods are entirely marine and are restricted to areas of sea floor with soft muddy substrates. They are unusual in the mollusc family because they lack ctendia (gills), a true heart, a true digestive gland and have no through-flow of water.

Scaphopods live their whole life buried, up to 30 cm (or several times their own body length) or more, below the sea floor and can be quite numerous in some habitats, up to 60 individuals per square meter of sea bed.

Basic Anatomy of the Scaphopoda

The animal has its whole body packed in a long thin cylinder. Strangely, despite the shell being open at both ends the animal has a U-shaped gut with both the mouth and the anus being situated near the anterior end of the shell.

The scaphopodan foot is reduced and described as bilobed in the dentaliidae and fringed in the gadilida. It is used to move the animal through the substrate and to create a feeding space within the substrate. In scaphopoda the foot can be drawn completely into the shell.

The scaphopda possess numerous unique organs called captacula around their mouth. The actual number varies between species ranging from 30 to 300 (and can vary between individuals to a lesser amount). These captacula are long thin filaments with a bulbous head, or distal end. They are contractile (can be shortened) and extensile (can be extended) as well as ciliated.

Captacula can be of various lengths in a single animal and can be easily lost and regrown. They apparently have some sensory capabilities but their main role in the scaphopod’s life is to bring food items into the animal’s mouth.

Scaphopods possess a large and well developed radula. However, unlike most molluscs, this radula cannot be extended out of the body. Instead it is used to break or crush the shells of the small creatures the scaphopod feeds on. The two different orders of scaphopoda have radula that function in different ways.

Blood and Blood Sinuses

The vascular system is of the scaphopoda is very rudimentary. Both a heart and blood-vessels are entirely missing. The blood/haemolymph is contained in sinuses which possess nothing in the way of distinct walls or endothelial lining. The four main sinuses are called; pallial, pedal, perianal and visceral. Contraction of the foot are used to pump the blood around the body.

Another unusual thing about Scaphopoda is that they are the only molluscs in which there is any direct communication between the blood-spaces and the external environment (sea water). This happens at a pair of apertures near the renal openings that lead from the perianal sinus to the exterior and allow the blood to escape during violent contractions of the body.

Respiration in Tusk Shells

Because the scaphopoda possess no gills or ctendia, as do other molluscs, the functions usually performed by these organs are performed by the internal surface of the mantle. Yet again the scaphopoda are unique in that they have no flow through of water (usually across the ctenidia). Instead fresh water is drawn into mantle cavity by the beating action of numerous cilia and about once every ten minutes or so. The deoxygenated water is expelled through the upper most end of the shell by a muscular contraction of the foot.

Water enters the mantle cavity by means of another unique scaphopodan development; the pavilion. This pavilion plays the role normally served by an inhalent syphon in other substrate borrowing molluscs. However it is not muscular in the way of the bivalve inhalent siphon. Furthermore, though it lacks osphradia, the organ typically used to sense water quality in aquatic molluscs, it does possess ciliated sensory receptors.

Feeding and Digestion

The scaphopoda feed by drawing food items into their body using an usual set of very fine, thread-like organs on the head called captacula.

Once food has been brought to, and broken up by the radula it is passed on to the stomach through the oesophagus. The scaphopod stomach is small and receives digestive juices from a pyloric ceca (which exists in place of the normal digestive ceca), it is also connected to the liver by one or two ducts.

From the stomach the food progresses to, and through, the intestine, which, reflecting the carnivorous habits of scaphopods, is relatively short.

Scaphopods feed mostly on smaller marine animals, in particular foraminifera, but also kinorhyncha, copepoda and ostracoda.

Nerves and Senses in Tusk Shells

The nervous system is relatively simple with a dispersed collection of ganglia connected by various nerve cords. Near the oesphagus there are a pair of both cerebral and pleural ganglia, these are the closest thing a scaphopod has to a brain. They also possess separate sets of pedal ganglia in the foot, and a pair of visceral ganglia near the center of the animal’s shell. Finally there are radular and sub-radular ganglia.

Scaphopods possess both statocysts with staticonia, presumably to assist them in orienting their bodies. However, they possess no eyes and no osphradia. Recent scientific research into the genetics of the species Antalis entalis suggests that scaphopoda evolved from ancestor molluscs that had eyes, but that they have since lost them.

Reproduction in the Scaphopoda

The Scaphopoda are dioecious, meaning they have separate males and females. Several hermaphroditic specimens of Dentalium entalis were reported in 1974 T. D’Anna, but this now appears to be a rare anomaly. Each individual possesses only a single gonad situated in posterior part of the body which shed their gametes into the water through the nephridiopore, thus fertilization is external.

The fertilized, the eggs soon hatch into a free-living trochophore larva, which in turn develops into a veliger larva. The veliger larva is more like the adult in appearance, but has not yet elongated into the characteristic scaphopod shape.

The Scaphopoda and Humanity

The tusks of some scaphopods were once used as money (often termed “wampum”) by American Natives of the Pacific Northwest from Alaska to California.

The shells were collected on to strings that could be worn and so resembled necklaces. In more modern times Tusk Shells are sold as trinkets, souvenirs and as jewelry.

The eggs of some species of scaphopoda ( particularly Dentalium entalis) are commonly used in scientific studies of embryonic development.

Image Credits: Cover Image by Daderot License – CC0 1.0; Scaphopod Shell Necklace by Rama License – CC BY-SA 2.0 Various other Scaphopod shells by H. Zell – License CC BY-SA 3.0