Phylum Phoronida (The Horseshoe Worms)

The Etymology of Phronida: Derived from Phoronis, another name for the Egyptian God Isis

Characteristics of Phoronida:

- Has bilateral symmetry.

- Has a body more than two cell layers thick with tissues and organs.

- Body is vermiform in shape.

- Has a U shaped gut with a mouth and anus.

- Body has 3 parts, prosome, mesosome, metasome

- Has a diffuse nervous system.

- Has a closed blood system, with Haemoglobin.

- Reproduction sexual and normally hermaphroditic, some gonochoristic.

- The eggs and larvae are often brooded within the body cavity or the secreted tube.

- Lives in marine environments.

Introduction

Phoronida (also known as Horseshoe worms) is a very small phylum, containing 11 species of generally small marine worms.

They are related to the other lophophorate phyla Brachiopoda and Bryozoa. They live in burrows lined with secreted tubes, mostly in shallow coastal waters. Normally the worm’s body remains hidden within their tubes and all you can see are the many thin tentacles that make the lophophore.

A few representative species are; Phoronopsis californica, a large (30cm / 1 ft long) orange-coloured species found along the west coast of North America; Phoronis architecta, a smaller (12cm / 4 in long) species the east coast of North America and Phoronis hippocrepia, found around most European coasts.

Though they are normally long (up to 50cm / 30 in) Phoronids are normally very thin.

Phoronopsis viridis for example is 20cm long but only 3mm (1/8 of an inch) in diametre. Many species are however much shorter than this, though they are all very thin – Phoronis psammophila is 5cm long and Phoronis gracilis only 1cm.

The prize for smallest species goes to Phoronis ovalis which measures only 6mm in length and which lives in colonies on the shells of oysters, where there may be as many as 150 animals per cm2.

The first adult Phoronids were described in 1856 by T. Stretill Wright from the English Channel (Phoronis hippocrepia and Phoronis ovalis). Although some research has been done on the ecology of Phoronids since then, we still know very little about the lives of most of these animals. Phoronids are also sometimes called Phoronans.

Phoronid Morphology and Ecology

Phoronans live in tubes which they secrete. These tubes can be buried in the mud or sand that makes up the sea bed. Or else they can be resting on the surface of a rocky substrate. In this case, they tend to live in colonies and their tubes become twisted around each other for support to form a large impenetrable mass.

Some species can dissolve away holes in rocks such as limestone, calcareous seashells or even cement piers. They then live in these holes which they line with their secreted tubes.

Because they live in tubes, Phoronids have U shaped guts or digestive tracts and the distance between their mouth and their anus is very small. The Phoronan body, like the body’s of the other lophophorates, has 3 main sections. However in Phoronans, as in the Brachiopoda, the anterior or front section is highly reduced. In Phoronans it consists only of a small lid which guards the oral cavity.

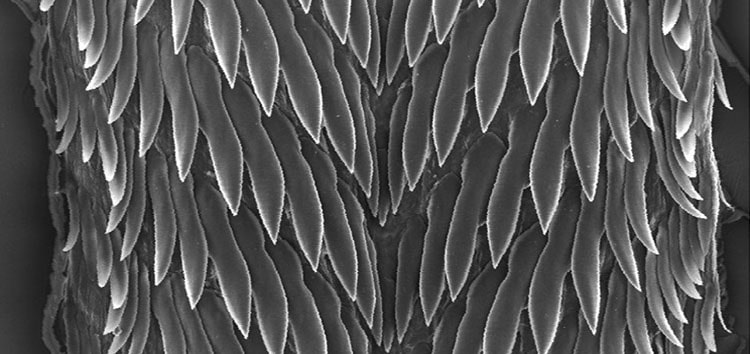

The visible portions of the body are the mesosoma and metasoma, which are separated internally by a septum. The mesosoma is the lophophore, normally the only part of the animal which is visible. The lophophore consists of between 1 and many hundreds of tentacles, depending on species.

Those species with many tentacles keep them displayed in a double coil that some authors say looks a bit like a horse-shoe (hence the common name “Horseshoe Worm”).

The tentacles have numerous cilia on them. These cilia beat to generate a current of water down from their tips towards the mouth. Food particles in the water current are trapped in a stream of mucous that travels along the tentacles until it reaches the oral ring, from where it is drawn into the mouth and then on into the digestive tract.

The digestive tract of Phoronids consists of a short oesophagus, which leads into a spherical stomach and then into the intestines – which end in the anus.

Phoronids have a simple blood system, comprising a single descending artery and ascending vein linked by a network of fine capillaries. There are also blood vessels into each of the tentacles. The blood of Phoronans is colourless but contains corpuscles with a haemoglobin like pigment which helps in carrying oxygen.

The tentacles act as gills or organs of gaseous exchange, as well as being used for feeding. Therefore the blood gains oxygen and loses carbon dioxide while it is passing through them. Metabolic wastes are extracted from the blood by means of a pair of tubular metanephridia situated on either side of the hindgut. The nervous system of Phoronids consists of a diffuse network of nerve which cover the entire body.

Phoronida are mostly hermaphroditic (meaning they are both male and female), but a few species are gonochoristic (meaning they are either male or female). Fertilisation is, as far as we know, internal. Phoronans generally follow one of two main types of reproductive strategies.

Some species, such as Phoronis ovalis, lay only a few (12 – 25) large eggs which have a lot of yolk. These eggs are brooded within the adults tube, then are released only when they have hatched. They do not feed and spend only about 4 days in the plankton as larvae. Then they sink to the sea floor where, after a further 3 days, they become permanently attached. Here they soon metamorphose into a small adult.

The second strategy is to lay a much larger number (up to 500) of smaller eggs. These eggs are released as soon as they are fertilised. They hatch a few days later into what is called an ‘actinotrocha’ larvae. This free swimming and feeding larvae remains a part of the seas plankton for about 3 weeks, before it too sinks to the sea floor and undergoes metamorphosis.

Phoronids can regenerate the lophophore if it becomes damaged, in fact Phoronis ovalis voluntarily loses its lophophore in order to lay its eggs. Once the eggs are laid the animal grows a new lophophore.

Phoronida Classification

The eleven known species of Phoronida are placed into two genera Phoronis, and Phoronopsis as follows:

- Phoronis australis

- Phoronis emigi

- Phoronis hippocrepia

- Phoronis ijimai

- Phoronis muelleri

- Phoronis ovalis

- Phoronis pallida

- Phoronis psammophila

- Phoronopsis albomaculata

- Phoronopsis californica

- Phoronopsis harmeri

Other pages on this site that might interest you include:- Phylum Entoprocta (Goblet Worms) and Phylum Cycliophora (Cycliophorans).