Wild Turkeys

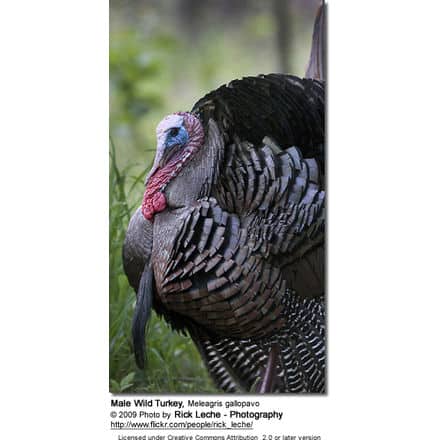

Wild turkeys are different than the domesticated white turkeys that are bred for food in the USA and other parts of the world.

Wild Turkeys are smaller than domesticated turkeys and far more colorful in appearance.

Turkey Information … Wild Turkey Description … Wild Turkey Reproduction / Breeding

Introduction to the Wild Turkey

By T.R. Michels – www.TRMichels.com

Range

Wild turkeys are resident in much of eastern North America, from extreme southern Canada southward to Mexico and Florida. They are scattered locally in the western states and have been introduced into many western states, and Hawaii, Europe, and New Zealand.

Habitat

Wild turkeys can be found in hardwood forests with scattered openings, swamps, mesquite grassland, ponderosa pine, and chaparral.

Food

Wild turkeys are opportunistic foragers. In wilderness and rural areas, they eat green vegetation, acorns, nuts, seeds, fruits, insects, buds, fern fronds, and salamanders. In agricultural areas, they eat new green shoots and seeds of crops, silage, hay, and bird and cattle feed.

Foraging Behavior

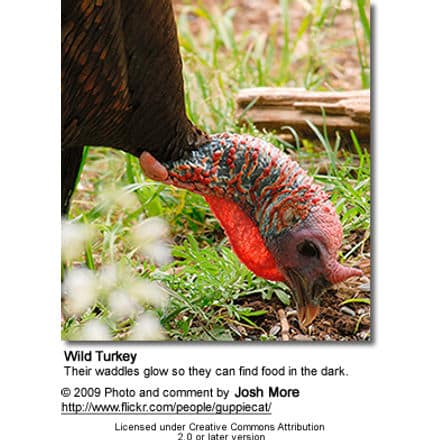

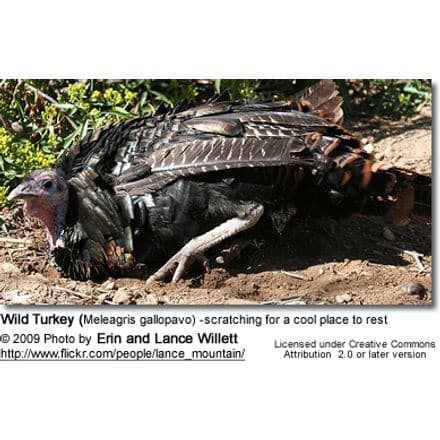

Wild turkeys forage on the ground, often scratching the ground to uncover vegetation seeds, nuts, berries, and insects.

Breeding / Reproduction

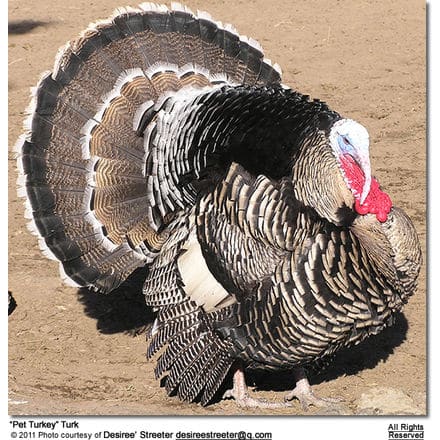

Male turkeys gobble, strut spit, and boom to attract females. During the strut the tail is fanned out and held up vertically, the wings are lowered so that the wingtips drag on the ground, and the feathers on the back and chest are fluffed out, with the head held back.

It may occasionally perform a deep “chump” (spit) sound, followed by a low “humm” (boom) accompanied by rapid vibration of the tail feathers.

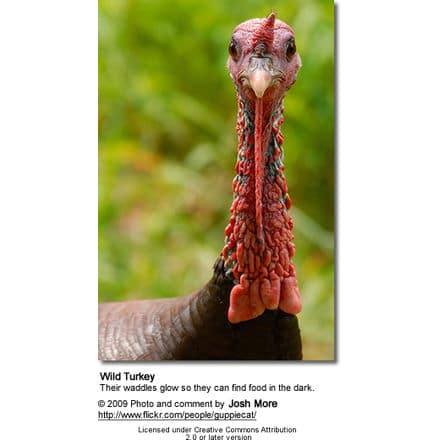

During the strut the facial skin engorges and the red, white, and blue colors intensify, especially the white area of the forehead.

The nest is a depression in dead leaves or vegetation on the ground that may contain from 4 to 17 tan or buffy white, evenly marked eggs with tiny reddish spots. The chicks hatch after an incubation period of 26 to 28 days. They are downy and able to follow the hen within minutes of hatching.

More information on wild turkey reproduction.

Conservation Status

Populations dropped drastically in the 19th and early 20th centuries because of hunting and habitat loss. Northeastern populations were eradicated.

Stocking programs successfully reintroduced turkeys to most of the eastern range, and areas outside the ancestral range in the West. Populations continue to increase.

Subspecies

There were originally six subspecies of the Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) in North America and one related species, the Ocellated Turkey (Meleagris ocellata) in Central America. The originally discovered subspecies (M. gallopavo gallopavo) is now extinct due to hunting.

Subspecies Distribution

The Eastern Turkey (M. g. silvestris) is the most widely distributed subspecies of the wild turkey. It occurs east of the Missouri River to the Atlantic Ocean, the southern and western parts of Minnesota, the eastern third of Kansas and Oklahoma, and eastern Texas and northern Florida.

The Florida subspecies (M. g. osceola) occur in the southern portion of Florida. The Rio Grande (M. g. intermedia) subspecies occurs mainly in the western portions of Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, with transplants in small portions of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Utah, and South Dakota.

The Merriam’s (M. g. merriami) subspecies occurs in South Dakota, and portions of most of the mountain states from Canada to Mexico.

The Rio Grande (M. g. intermedia) subspecies occurs mainly in the western portions of Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, with transplants in small portions of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Utah, and South Dakota.

The Gould’s Turkey (M.g. mexicana) occurs in extreme southwest New Mexico, southeast Arizona, and adjacent regions of Mexico. It is listed on the endangered species list; hunting is prohibited in the United States.

Hybrid or intergrade turkeys are found in areas where two or more subspecies occur; these birds may exhibit characteristics of one or the other subspecies, characteristics of both subspecies or characteristics between the two subspecies.

Wild Turkey Biology and Behavior

Habitat Generally speaking, the Eastern turkey is found in open, mixed hardwood and pine forests, the Osceola turkey is found in the subtropical regions of Florida, the Rio Grande turkey is found in the scattered brushland of the southwest, and the Merriam’s and Gould’s turkeys are found in the pine forests of the southwest.

Wild Turkeys prefer to roost in trees larger than the surrounding vegetation and will often choose roost sites on east-facing slopes out of the prevailing winds.

Because sight is one of the turkeys’ means of defense against predators, they often use open fields and meadows as feeding and strutting sites, and wooded areas as roosting sites. Strutting sites are often traditional, used year after year by successive birds.

Foraging

Wild Turkeys eat a wide range of foods including succulent grasses and Forbes, insects, leftover grains, fruits of the grape, cherry, and black gum, seeds including mast crops of acorns, pine nuts, and juniper (cedar) berries, and new growth crops. In the winter turkeys rely heavily on acorns and seeds; branch tips of brush and trees; and leftover grain crops; and will feed heavily in fields where manure has been spread; at corn cribs and feedlots; and silage piles.

In the early spring turkeys often rely on leftover grain in agricultural fields. Once the weather warms and new green growth appears they will begin feeding in pastures, river and creek bottoms, and hayfields, where they eat green forage and search for insects.

Hens often seek out sources of calcium (such as land snails) for egg production in the spring.

Roosts

The availability and location of turkey roosting sites is a determining factor in turkey use of the habitat. If few or no roosting sites are available turkeys may leave the area or not use it. They prefer to roost in heavy timber in ravines if possible; where they can be out of strong prevailing winds in winter, but they will roost in trees open to the wind. Roost sites are often located over or near water in the south.

Scientific studies have shown that turkeys often roost on an east or south-facing slope, about a third of the way down the slope where the winds are calm. East and south-facing slopes also receive the earliest sunlight, allowing the birds to warm upone-half and be able to see early in the morning.

In one study roost sites were often within one half mile of water, and five hundred yards of a meadow. This could be attributed to the fact that turkeys often feed before going to roost in the evening, and they don’t travel far at dusk.

The preferred roosts in the study were mature trees with open crowns giving the turkeys room to fly into the trees and move around. They also preferred trees with large horizontal limbs to roost on.

In western areas, turkeys use fir, pine, spruce, cottonwood, and large aspen trees as roosts. Eastern birds often choose pines, elm, maple, box elder, large oak, and cottonwood.

Mature toms often choose pines (where they are available) because the pines can reduce wind speeds by 50-70 percent. Eastern turkeys generally have several roost sites in their home range, and they may use different sites on successive nights.

In limited and poor habitats, Merriam’s turkeys often roost in the same trees regularly.

Vision

Vision scientist Dr. Jay Neitz believes that most birds see in trichromatic color like humans and that some birds see ultraviolet light as different than any of the three primary colors of red, yellow, and blue seen by humans.

Birds detect ultraviolet light in low light conditions that humans can’t detect ultraviolet light, especially birds that are nighttime predators.

Because turkeys are a prey species their eyes are located on the sides of the head, giving them a wide field of vision.

But, because of their wide-spaced eyes, they sacrifice depth perception; they see very little in front of them with both eyes at the same time. As turkeys walk, their heads move back and forth, giving them two different angles of an object, which helps them determine the distance to the object.

As a result of their poor depth perception, turkeys have difficulty determining the relative size of objects.

Hearing

The ears of most birds, including turkeys, are located on the sides of their heads, and because they have no outer ear with a cup to enhance the sound from one direction, they hear sounds around them.

Sound received by one ear but not by the other ear helps the birds determine which direction the sounds come from, but not the distance of the sound. Loud sounds generally come from a closer range than quieter sounds, and cause turkeys to become alert.

This explains why prey species with widely spaced eyes and ears, like turkeys, often try to verify the danger with both their eyes and ears, and then give an alarm signal before fleeing.

If they don’t know which direction the danger came from they need to verify the danger, and its direction, before they flee; or they may flee into, rather than away from, the danger.

Smell

Mammalian prey species (deer, elk, sheep, etc.) that have a highly developed sense of smell can determine the direction of danger by scent and wind direction.

They generally flee downwind or crosswind from danger, knowing they are fleeing away from danger, not toward it.

Because most birds have a poor sense of smell they need to rely heavily on both their eyes and their ears to determine the direction of danger before they flee from it.

Signs of Turkeys

Turkeys leave a variety of signs as an indication of their presence. Adult turkey tracks range from 2-3 inches in length, hens up to 2 1/8 inches, and toms up to 2 1/4 inches and longer.

Mature toms leave a wider and deeper middle toe imprint than hens, often with the scales of the toes showing in the track.

Turkey droppings can be found under roost trees, in feeding areas, and along travel routes. Hen droppings are pencil-sized or larger and are bulbous or spiral-shaped; tom droppings are straight or “J” shaped.

Piles of droppings under large trees indicate roost sites. Dropped feathers, wing scrape marks in strutting areas, and the shallow depressions of turkey dusting bowls are all evidence of turkey use. V-shaped scratches in dirt or leaf litter are evidence that turkeys have been feeding in the area.

Social Structure

Turkeys habitually occur in flocks. The hens and the young poults often stay together throughout the summer in family groups, or flocks of several families, with an older hen as the dominant bird of each family, and possibly of each group.

Young females often stay with their mothers through the winter and may join other “female” family groups until spring.

In the fall the young males or “jakes” form their flocks and stay together through the winter. These groups of jakes may join adult males in the spring; during the breeding season.

Adult male flocks often form in the summer after the breeding season is over. These male groups often remain together until spring, when some of the toms go off by themselves.

However, toms may form small groups of two or more birds during the breeding season; I have seen as many as six toms in one group. several groups of gobblers may ally and fight other groups of gobblers for dominance and breeding rights.

Since dominance is established within each family as the young birds grow, and the male siblings of each family often stay together into adulthood, the dominant male of each group is often the sibling of the other males in the group.

Author: T.R. Michels,www.TRMichels.com

Beauty Of Birds strives to maintain accurate and up-to-date information; however, mistakes do happen. If you would like to correct or update any of the information, please contact us. THANK YOU!!!