Swallow-tailed Hummingbirds

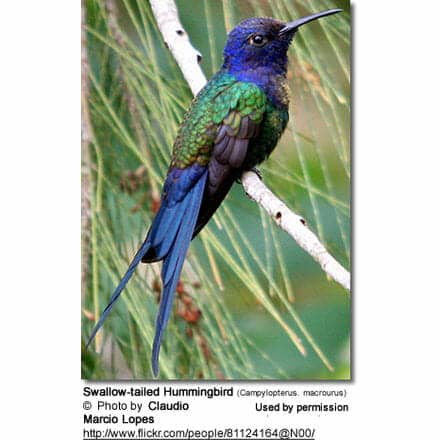

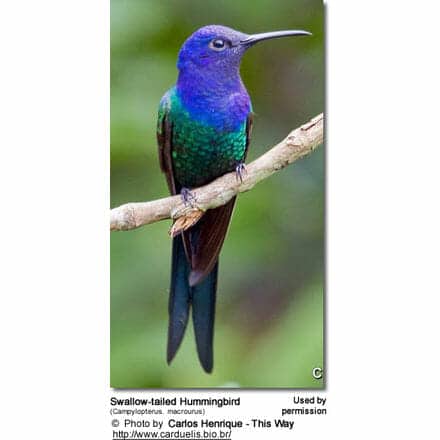

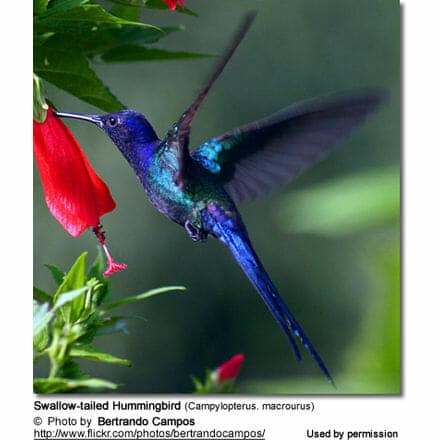

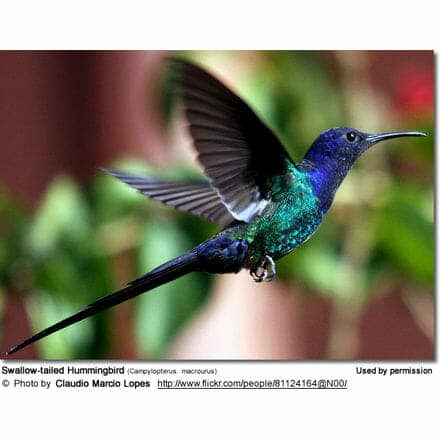

The Swallow-tailed or Cayenne Fork-tailed Hummingbird (Campylopterus macrourus) is also known as Common or Brazilian Swallowtail. Its common name was derived from its long, deeply forked, somewhat swallow-like tail.

It occurs naturally in east-central South America.

Some authorities place this species in the genus Eupetomena, but based on its song structure and enlarged shafts of the male’s first primary flight feathers it is now mostly considered to be part of the Campylopterus.

Alternate (Global) Names

Spanish: Colibrí Golondrina, Picaflor golondrina, Picaflor tijereta … Portuguese: beija-flor-cauda-de-andorinha, beija-flor-grande, beija-flor-preto, Beija-flor-rabo-de-tesoura, beija-flor-tesoura, Tesourao, tesourão .. French: Colibri hirondelle … Czech: Kolibrík vlaštovcí, kolib?ík vlaštov?í … Danish: Svalehalekolibri … German: Blauer Gabelschwanzkolibri, Breitschwingenkolibri, Breitschwingen-Kolibri … Estonian: pääsukoolibri … Finnish: Pääskypyrstökolibri … French: Campylopterus macrourus, Colibri à queue d’hirondelle, Colibri hirondelle …Guarani: Mainumby jetapa …Italian: Colibrì coda di rondine, Colibrì codadirondine …Japanese: tsubamehachidori …Dutch: Zwaluwstaartkolibrie … Norwegian: Svalekolibri … Polish: smigacz, ?migacz … Russian: ????????? ???????, ???????????? ??????? … Slovak: kolibrík lastovicí, Kolibrík lastovi?kovitý …Swedish: Svalstjärtskolibri

Distribution / Range

They generally occur in lowland areas, but may move up locally to 1,500 m (4,900 ft). They can be found in:

- Brazil:

- the Caatinga (xeric shrubland and thorn forests) and Cerrado (tropical savannas). They are found in virtually any semi-open habitats, including gardens and parks within large cities, such as Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.

- In southern Brazil, their numbers have been increasing and they appear to have extended their range in recent decades.

- In south-eastern Brazil, they are common in urban parks and gardens,

- Adjacent parts of northern and eastern Bolivia; coastal regions in Santa Catarina.

- Far northern Paraguay

- The coastal regions from French Guiana

- Southeastern Peru: upper Urubamba River and Pampas del Heath)

- Southern Suriname (Sipaliwini savanna)

- In the Amazon Basin, they are mostly found along the southern and eastern edge, in the open habitats along the lowermost sections of the Amazon River, including Marajó Island, and upstream to around the Tapajós River.

Hummingbird Resources

- Hummingbird Information

- Hummingbird Amazing Facts

- Attracting Hummingbirds to Your Garden

- Hummingbird Species

- Feeding Hummingbirds

They are mostly resident (non-migratory), but some may travel north or south a short distance during the dry winter months.

This species is among the commonest species throughout most of its range. However, it is generally is uncommon to rare in the outlying regions, particularly where it is humid.

Conservation: Up to 1970, these birds were exported for the cage trade; however, this species is now protected under CITES Appendix II, which restricts its trade.

Description

The Swallow-tailed Hummingbird is one the largest hummingbirds within much of its range – measuring 6 – 6.5 inches or 15–17 cm including beak and tail. Nearly half of its length is made up by its tail. Its wings are close to 3.15 inches or 8 cm long. However, its slightly down-curved black bill is only of 2.1 cm or 0.83 inches. It averages 0.32 oz or 9 g in weight.

Males: The plumage is mostly a brilliant iridescent green; except the head, upper chest, tail and vent are a deep blue-violet; and the remiges (flight feathers) are blackish-brown.

The tiny white spot behind the eye is common among hummingbirds; however, it is often not visible in the Swallow-tailed.

They have well-developed white ankle tufts. The dark blue tail is long and deeply forked,

Females resemble males; except females are about one-fourth smaller than males and their plumage is slightly duller.

Juveniles look like females, but the head is particularly dull and brownish-tinged.

Subspecies Differences: The five recognized subspecies vary mainly in the hue of the plumage. The blue variations range from green-tinged blue over ultramarine to deep royal blue. The green variations range from golden bronzy-green to deep bottle-green or blue-tinged green.

Similar Species: Could be confused with the male Violet-capped Woodnymph (Thalurania glaucopis); however they can be distinguished by their blue caps.

Subspecies, Distribution and Identification:

The nominate race and the subspecies Campylopterus macrourus simoni occur over a wide range. The other subspecies are more localized.

- Campylopterus macrourus macrourus (J. F. Gmelin, 1788) – Nominate Race

- Found in the Guianas and north, central and southeasternBrazil (Amapá and north and south Pará; Mato Grosso, southwestern Goiás and Minas Gerais to São Paulo) to Paraguay.The nominate race’s range overlaps with the subspecies “simoni” in the states Goiás (central Brazil) and Minas Gerais (southeastern Brazil).

- ID: The blue parts are ultramarine. The green parts are deep bottle-green.

- Campylopterus macrourus simoni (Hellmayr, 1929)

- North-east Brazil from south Maranhão, Piauí, Ceará, Pernambuco and Bahia to central Goiás and Minas GeraisThe bluest subspecies. The plumage below and on the back are more bluish-green than that of the nominate subspecies. The blue parts are dark royal blue. The green parts are blue-tinged.

- Campylopterus macrourus cyanoviridis (Grantsau, 1988)

- Southeastern Brazil in Serra do Mar in southernSão PauloA very green subspecies. The blue parts are green-tinged. The green parts are golden bronzy green.

- Campylopterus macrourus hirundo (Gould, 1875)

- Eastern Peru (Huiro)

- A dull blue color. The tail is less deeply forked

- Campylopterus macrourus bolivianus (Zimmer, 1950)

- Northeastern Bolivia (Beni Department)The greenest subspecies. Its head is more green than blue. The green parts are bright green.

Calls / Vocalizations

Their vocalizations include loud psek notes and weaker twitters. When alarmed or excited, tik calls can be heard.

Nesting / Breeding

Hummingbirds are solitary in all aspects of life other than breeding, and the male’s only involvement in the reproductive process is the actual mating with the female. They neither live nor migrate in flocks, and there is no pair bond for this species.

They breed throughout the year; however, most nest activities occur from July and September, and then again in December.

The male courts the female by hovering in front of the perched female, chasing her through the air and the two may perform a ‘zig-zag flight’ together. The male hovering in front of the female can be seen throughout the day except in the hottest part of the day. However, the courtship chases usually happen at dusk.

He will separate from the female immediately after copulation. One male may mate with several females. In all likelihood, the female will also mate with several males. The males do not participate in choosing the nest location, building the nest or raising the chicks.

The female is responsible for building the cup-shaped nest out of plant fibers woven together and green moss on the outside for camouflage in a protected location in a shrub, bush, or smallish tree – typically below 10 ft (3 m), but occasionally as high as 50 ft (15 m) above the ground. She lines the nest with soft plant fibers, animal hair, and feathers down, and strengthens the structure with spider webbing and other sticky material, giving it an elastic quality to allow it to stretch to double its size as the chicks grow and need more room. The nest is typically found on a low, thin horizontal branch.

The average clutch consists of one white egg, which she incubates alone for about 15 to 16 days, while the male defends his territory and the flowers he feeds on. The dark-skinned young are born blind and immobile and only have some grey down on the back. The feathers start emerging about 5 days or so after hatching they start to grow feathers five days or so after hatching, starting with the flight feathers on the wings (remiges). The long flight feathers of the tail (rectrices) begin to emerge about three days later.

The female alone protects the chicks. In a study of a nest in urban São Paulo, it was noted that the Swallow-tailed mother drove away Ruddy Ground Doves attempting to nest nearby. Even though the Ruddy Ground Drove themselves didn’t present a danger to the young, these birds attract carnivores and by chasing them away, the hummingbird reduces the risk of predators coming closer to the nest and preying on her young.

During the breeding season, in particular, they will” dive-bomb” birds twice their size. When they are disturbed by much larger birds such as Guira Cuckoos or hawks, they usually only give warning calls, however, one female Swallow-tailed hummingbird has been observed to actually attack a Swainson’s Hawk – weighing more than a hundred times as much as a hummingbird – in mid-air. Warning calls are also given to other animals (mammals), including humans. Although in an urban environment, they have learned to tolerate human observers even when nesting; as long as they keep a distance of 30 feet (10 meters) or more from the nest.

The female feeds the young with regurgitated food about 1 to 2 times an hour (mostly insects since nectar is an insufficient source of protein for the growing chicks). As is the case with other hummingbird species, the chicks are brooded only the first week or two and are left alone even on cooler nights after about 12 days – probably due to the small nest size.

The chicks leave the nest when they are about 22 – 24 days old but will return to the nest to sleep for some more days. They will be independent about 2 -3 weeks after fledging. The young are of breeding age when they are about 1 to 2 years old.

The female may raise two broods in a season, sometimes reusing the nest.

Diet / Feeding

They primarily feed on flower nectar taken from a variety of brightly colored, scented small flowers of trees, herbs, shrubs and epiphytes, such Fabaceae, Gesneriaceae, Malvaceae (especially Bombacoideae and Malvoideae), Myrtaceae, Rubiaceae and epiphytic Bromeliaceae. They are not specialized feeders, however, and may also take the nectar of related families, such as Asteraceae or Caryocaraceae.

They feed on native plants as well as introduced ornamental plants.