-

ENGAGEMENT RINGS

- Start with a Setting

- Start with a Diamond

- Start with a Lab Grown Diamond

- Start with a Gemstone

- Start with a Bridal Set

SHOP BY SHAPEFEATUREDTHE BRILLIANT EARTH DIFFERENCE

-

WEDDING RINGS

- Women's Wedding Rings

- Diamond Rings

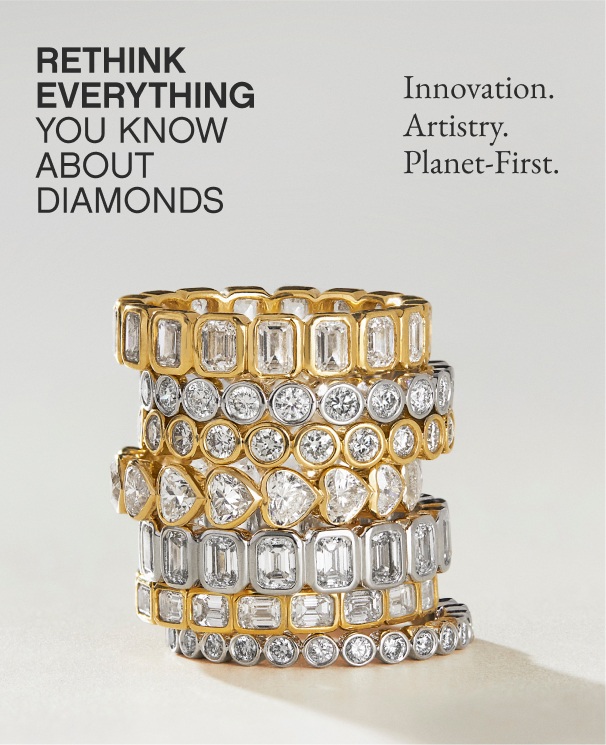

- Design Your Own Ring Stack

- Find My Matching Wedding Ring

- Eternity Rings

- Anniversary Rings

- Curved Rings

- Wedding Ring Sets

- Men's Wedding Bands

- Classic Bands

- Men's Engagement Rings

- Customize Your Own Ring

- Diamond Bands

- Matte Bands

- Hammered Bands

- Men's Jewelry

WOMEN'S BY METALMEN'S BY METAL -

DIAMONDS

- Search Lab Diamonds

- Lab Colored Diamonds

- Carbon Capture Lab Diamonds

- 100% Renewable Energy Lab Diamonds

- Sustainably Rated Lab Diamonds

- Custom Cut Lab Grown Diamonds

FEATURED- Design Your Own Diamond Ring

- Design Your Own Lab Diamond Ring

- Design Your Own Diamond Earrings

- Design Your Own Diamond Necklace

DIAMOND JEWELRYTHE BRILLIANT EARTH DIFFERENCE -

GEMSTONES

- Start with a Gemstone

- Start with a Setting

- Sapphire

- Moissanite

- Emerald

- Aquamarine

- Alexandrite

- Colored Diamond

- Ruby

- Morganite

PRESET GEMSTONE RINGSFEATURED -

JEWELRY

- Earrings

- Necklaces

- Rings

- Bracelets

- Men's Jewelry

- Lab Diamond Jewelry

- Birthstone Jewelry

- Gemstone Jewelry

- Pearl Jewelry

- Diamond Jewelry

SHOP BY STYLEDESIGN YOUR OWNJEWELRY COLLECTIONS -

GIFTS

TOP GIFTS

- Gifts Under $250

- Gifts Under $500

- Best Selling Gifts

- Diamond Stud Earrings

- Tennis Bracelets

- Gemstone Rings

- Stacking Rings

- Gold Jewelry

- Jewelry Sets

- Hoop Earrings

- Bezel Jewelry

GIFTS BY RECIPIENTGIFTS BY OCCASIONGIFTS WITH MEANINGDESIGN YOUR OWNMORE GIFT IDEAS -

ABOUT

FEATURED GUIDES