Canvasbacks

The Canvasbacks (Aythya valisineria) is a large North American diving duck, that ranges from between 48–56cm long and weighs approximately 862-1588 g, with a wingspan of 79-89 cm.

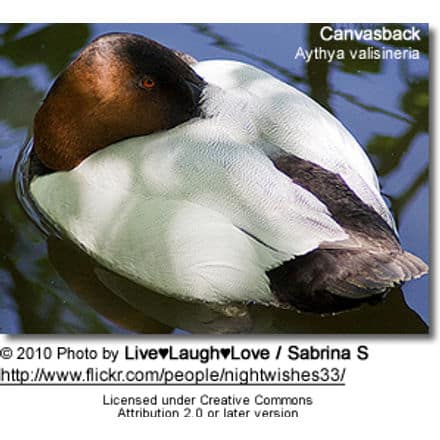

The adult male has a black bill, a chestnut red head and neck, a black breast, a grayish back, black rump, and a blackish brown tail. The sides, flank, and belly are white while the wing coverts are grayish and vermiculated with black. The bill is blackish and the legs and feet are bluish-gray. The iris is bright red in the spring, but duller in the winter.

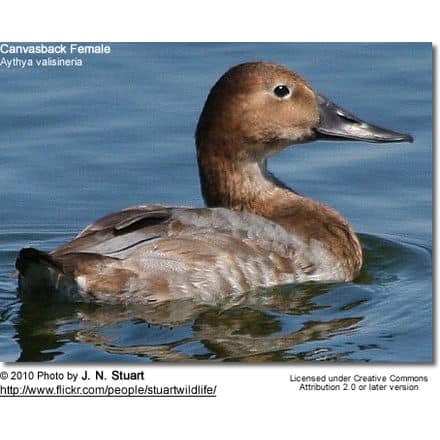

The adult female have a light brown head and neck, grading into a darker brown chest and foreback. The sides, flanks, and back are grayish brown. The bill is blackish and the legs and feet are bluish-gray. Its sloping profile distinguishes it from other ducks.

The species name of the Canvasback, Aythya valisineria, comes from Vallisneria americana, or wild celery, whose winter buds and rhizomes are its preferred food during the nonbreeding period. The duck’s name is based on early European inhabitants of North America’s assertion that its back was a canvaslike color. The French call the canvas back the Morillon à dos blanc, and the Spanish refer to it as Pato coacoxtle.

More Duck Resources

Breeding

Their breeding habitat is in North America prairie potholes. The bulky nest is built from vegetation in a marsh and lined with down. Loss of nesting habitat has caused populations to decline.

Canvasbacks usually take new mates each year, pairing in late winter on ocean bays. They prefer to nest over water on permanent prairie marshes surrounded by emergent vegetation, such as cattails and bulrushes, which provide protective cover. Other important breeding areas are the sub-arctic river deltas in Saskatchewan and the interior of Alaska.

The canvasback sometimes lays eggs in other canvasback nests. It has a clutch size of approximately 5-11 eggs that are a greenish drab. The chicks are covered in down at hatching and able to leave the nest soon after. Female redheads often parasitize canvasback nests.

Migrating and Wintering

Canvasbacks migrate through the Mississippi Flyway to wintering grounds in the mid-Atlantic United States and the Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley (LMAV), or the Pacific Flyway to wintering grounds along the coast of California. Historically, the Chesapeake Bay wintered the majority of canvasbacks, but with the recent loss of submerged aquatic vegetation in the bay, their range has shifted south towards the LMAV. Brackish estuarine bays and marshes with abundant submergent vegetation and invertebrates are ideal wintering habitat for canvasbacks.

Diet

Canvasbacks feed mainly by diving, sometimes dabbling, mostly eating seeds, buds, leaves, tubers, roots, snails, and insect larvae. Canvasback ducks traditionally depended on the tubers of wild celery (Vallisneria americana) for food during migration and over the winter. This relationship is reflected in their scientific names. The canvasback’s large webbed feet are adapted for diving and their bills are designed for digging the tubers out of the substrate. In the late 1930s, studies showed that four-fifths of the food eaten by canvasbacks was plant material.

In the early 1950s there were 225,000 canvasbacks wintering in the Chesapeake Bay; this represented one-half of the entire North America population. By 1985, there were only 50,000 ducks wintering on the Chesapeake or one-tenth of the population. Canvasbacks were extensively hunted around the turn of the century, but federal hunting regulations restrict their harvest, so hunting was ruled out as a cause for the decline. Scientists have now concluded that the decline in duck populations was due to the decline in Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) acreage. An interesting thing has happened, however. While nowhere as common as they once were, the population of canvasbacks has stabilized and is even increasing slightly. Studies have now shown that by the 1970s four fifths of the ducks’ diet was made up of Baltic clams, which are very common in the Chesapeake Bay. The ducks have been able to adapt to the decline in SAV by changing their diet. Unfortunately, redhead ducks, which also feed on SAV tubers, have not been able to adapt, and their population remains low.

Conservation

Populations have fluctuated widely. Low levels in 1980s put the Canvasback on lists of special concern, but numbers increased greatly in the 1990s.

Many species of ducks, including the canvasback, are highly migratory, but are effectively conserved by protecting the places where they nest, even though they may be hunted away from their breeding grounds. Protecting key feeding and breeding grounds can be used to conserve other highly migratory species.