Veraguan Mango (Anthracothorax veraguensis)

Veraguan Mangos (Anthracothorax veraguensis) is a Central American hummingbird that was formerly considered conspecific (a member of the same species) with the Green-breasted Mango; however, in 1983 these two species were split up by the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU) based on some geographical and physical differences.

Other Names (Scientific and Global):

The scientific name of this hummingbird “Anthracothorax veraguensis” (Reichenbach, 1855) was derived from the region the first specimen was found in, namely in the Veragua province of Panama.

Spanish: Mango de Veragua; Italian: Mango di Veraguas; German: Veragua-Mangokolibri; Czech: kolib?ík panamský; Danish: Veraguamango; Finnish: panamanhohtokolibri; Japanese: panamamango-hachidori; Dutch: Veragua-mango; Norwegian: Blåstrupemango; Polish: weglik panamski; Slovak: jagavicka panamská; Swedish: Veraguamango

Distribution / Range

They have historically only been found in Panama in Central America; where they are resident in the Pacific lowlands of western Panama – from Chiriqu east to southern Coc, and along the Caribbean slope in Bocas del Toro and the Canal area. Their natural habitats are the secondary and gallery forests in the tropical zone.

In recent years, they appear to have expanded their territory to southwestern Costa Rica. Steven and Kevin Easley of Costa Rica Gateway were able to observe various individuals in a garden located in the port town of Golfito located in the Puntarenas Province on the southern Pacific Coast of Costa Rica, near the border of Panama.

The Veraguan Mangos was included in the 2009 national bird inventory by experts of the Costa Rican Ornithological Association.

The Veraguan Mangos has been part of the endangered species list since July 2006.

Description

Size:

They average 105 mm or 4.1 inches in length (not including the beak and the tail). Their length ranges between 99 – 11 mm (3.9 – 4.4 inches). Their wingspan is about 67.1 mm or 2.6 inches; the tail is about 36.5 mm or 1.4 inches. Its beak is almost as long as its body.

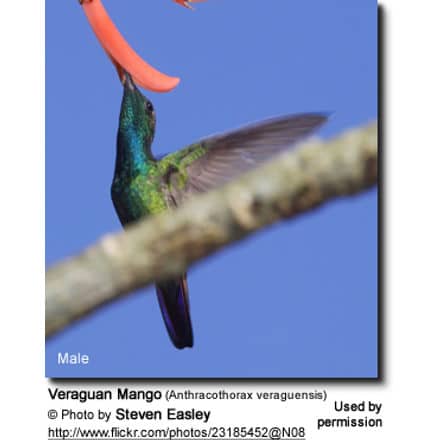

Adult Male:

The male’s upper plumage ranges from metallic bronze, greenish bronze to bronze-green. His neck is frequently bluish-colored.

The middle tail feathers are usually a coppery bronze. The other tail feathers are purplish maroon, glossed with violet-purple, and margined terminally with purplish or bluish-black. The wing feathers are brownish slate or dusky.

The face and throat are a brilliant metallic yellowish emerald green varying to more golden green.

The chest and median portion of the breast and belly are duller and more bluish-green. The sides are metallic bronze to bronze green.

The bill is dull black; the feet are dusky and the irises are brown.

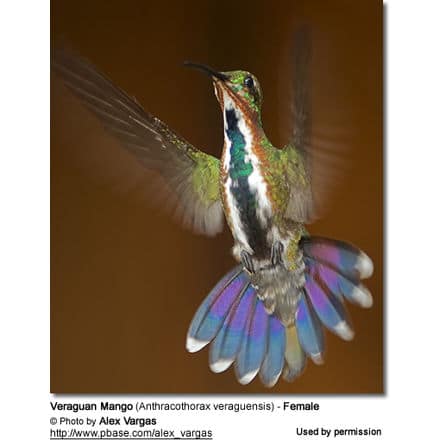

Adult Female:

The female has a similar upper plumage to the male. She has broad white stripes extending from her chin along the sides of the throat and chest down to the vent. Those white stripes enclose a metallic bluish-green stripe, the feathers of which are dusky beneath the surface

The sides of the neck down to her sides are metallic bronze-green. Her undertail feathers are light bronze-green narrowly tipped white. Her outer tail feathers are also white-tipped and crossed by a broad band of glossy blue-back; the remaining portion is chestnut colored glossed with metallic purple.

Similar Species:

The Green-breasted Mangos looks very much like the Colombian Veraguan Mangos; however, the Veraquan has a blue median stripe down the breast – while the Green-breasted’s median stripe is black – this applies to both males and females. Young Veraguans have a “more blackish” stripe than their parents, making them difficult to differentiate from the Green-breasted immatures.

Nesting / Breeding

Hummingbirds are solitary in all aspects of life other than breeding, and the male’s only involvement in the reproductive process is the actual mating with the female.

They neither live nor migrate in flocks, and there is no pair bond for this species. Males court females by flying in a U-shaped pattern in front of them. He will separate from the female immediately after copulation.

One male may mate with several females. In all likelihood, the female will also mate with several males. The males do not participate in choosing the nest location, building the nest, or raising the chicks.

The female is responsible for building the tiny cup-shaped nest out of plant fibers woven together and green moss on the outside for camouflage in a protected location in a shrub, bush, or tree (or as can be seen on the image to the right – they may take advantage of man-made structures).

She lines the nest with soft plant fibers, animal hair, and feathers down, and strengthens the structure with spider webbing and other sticky material, giving it an elastic quality to allow it to stretch to double its size as the chicks grow and need more room. The nest is typically found on a low, skinny horizontal branch.

The average clutch consists of two white eggs, which she incubates alone for about 16 to 17 days, while the male defends his territory and the flowers he feeds on. The young are born blind, immobile, and without any down.

The female alone protects and feeds the chicks with regurgitated food (mostly partially digested insects since nectar is an insufficient source of protein for the growing chicks). The female pushes the food down the chicks’ throats with her long bill directly into their stomachs.

As is the case with other hummingbird species, the chicks are brooded only the first week or two and are left alone even on cooler nights after about 12 days – probably due to the small nest size. The chicks leave the nest when they are about 24 days old.

Their nests have been observed on trees that were beset with Pseudomyrmex stinging ants. It is possible that these hummingbirds deliberately select such trees for nesting in order to deter predators.

Diet / Feeding

They primarily feed on nectar taken from a variety of brightly colored, scented small flowers of trees, herbs, shrubs, and epiphytes. They favor flowers with the highest sugar content (often red-colored and tubular-shaped) and seek out, and aggressively protect, those areas containing flowers with high-energy nectar. Their favorite nectar sources include the flowers of large trees, such as Inga, Erythrina, and Ceiba or kapok.

They use their long, extendible, straw-like tongues to retrieve the nectar while hovering with their tails cocked upward as they are licking at the nectar up to 13 times per second. Sometimes they may be seen hanging on the flower while feeding.

Many native and cultivated plants on whose flowers these birds feed heavily rely on them for pollination. The mostly tubular-shaped flowers actually exclude most bees and butterflies from feeding on them and, subsequently, from pollinating the plants.

They may also visit local hummingbird feeders for some sugar water, or drink out of bird baths or water fountains where they will either hover and sip water as it runs over the edge; or they will perch on the edge and drink – like all the other birds; however, they only remain still for a short moment.

They also take some small spiders and insects – important sources of protein particularly needed during the breeding season to ensure the proper development of their young. Insects are often caught in flight (hawking); snatched off leaves or branches, or taken from spider webs. A nesting female can capture up to 2,000 insects a day.

Males establish feeding territories, where they aggressively chase away other males as well as large insects – such as bumblebees and hawk moths – that want to feed in their territory. They use aerial flights and intimidating displays to defend their territories.

Calls / Vocalizations

Veraguan Mangos call is described as a high-pitched tsup, and the song is a buzzing kazick-kazee-kazick-kazee-kazick-kazee-kazick-kazee.

Metabolism and Survival and Flight Adaptions – Amazing Facts

Beauty Of Birds strives to maintain accurate and up-to-date information; however, mistakes do happen. If you would like to correct or update any of the information, please contact us. THANK YOU!!!